B-25 Mitchell — Birth of a Gunship

August 22nd, 2023

8 minute read

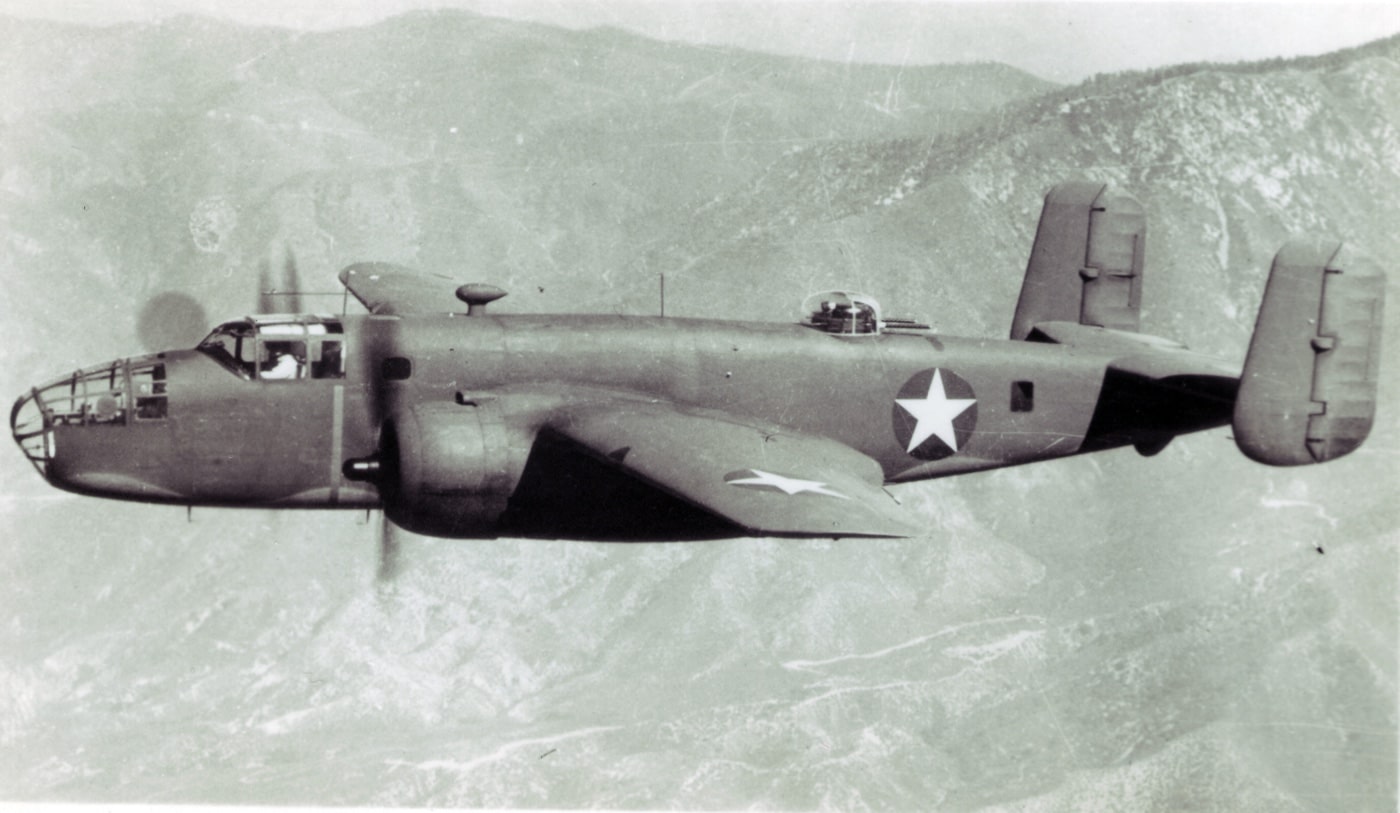

The North American B-25 Mitchell proved to be a remarkably flexible and adaptable aircraft. B-25 Mitchells shot to instant fame with the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo months after Pearl Harbor. But, the planes proved useful in other roles as well. The hard-pressed U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) squadrons stationed in the Southwest Pacific turned their medium bomber Mitchells into a powerful new form of ground attack aircraft: the gunship.

The gunship concept grew out of a pressing need to eliminate Japanese merchant ships supplying their far-flung empire, and to savage enemy airbases among the Solomon Islands. While the B-25 was developed to bomb from medium altitudes in level flight, it offered good performance at low altitude and provided a stable gun platform.

New tactics evolved almost instantly, and the B-25 crews modified their aircraft to get the most devastating results in their new strafing, skip bombing, and “parafrag” dropping missions.

Bomber Raids — Bring Enough Gun

In the low-level ground attack and strafing roles, the most visible changes manifested themselves in the B-25’s armament.

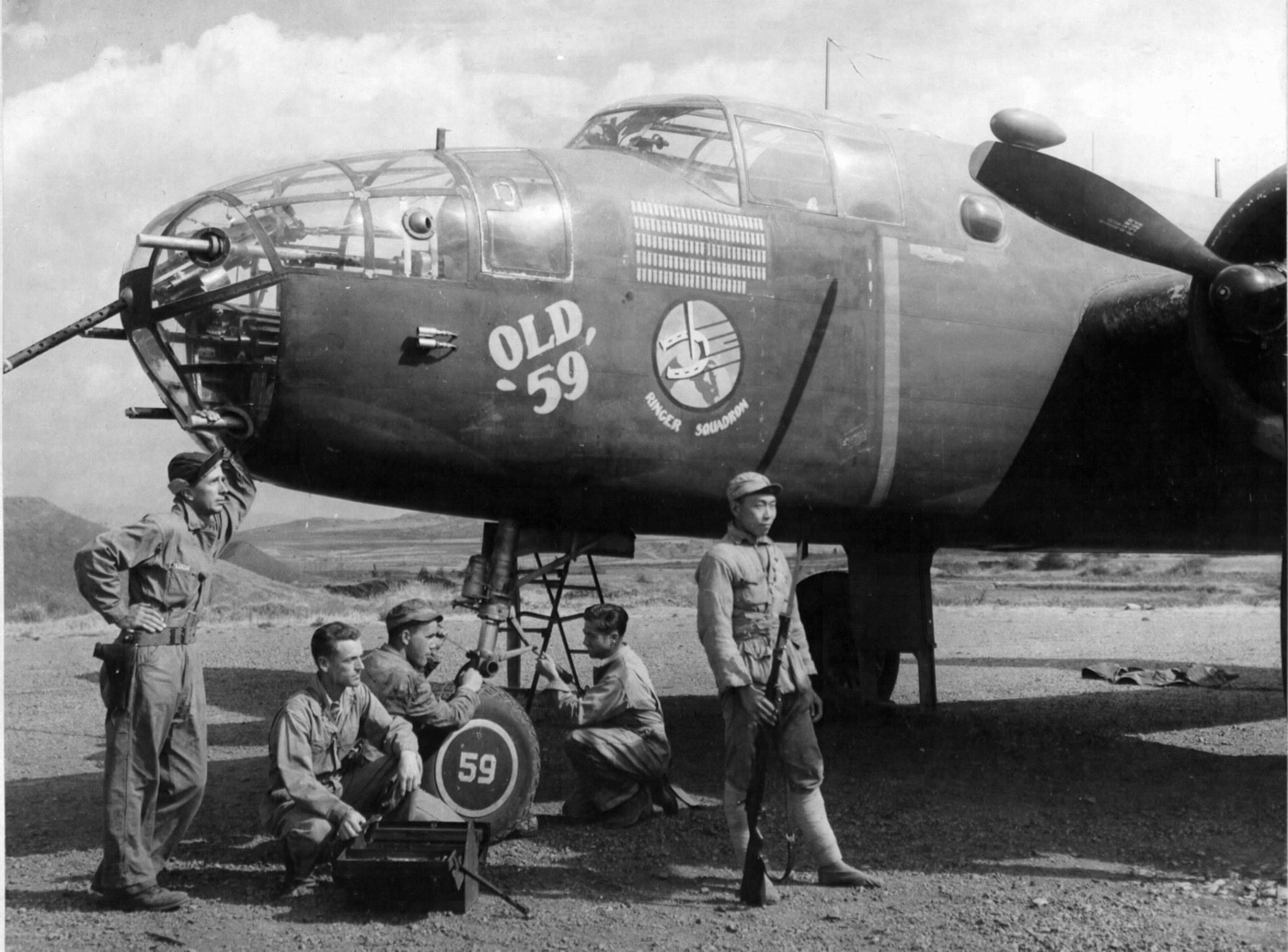

Lieutenant Colonel Paul “Pappy” Gunn, working with North American Aircraft (the maker of the B-25) field representative Jack Fox, began to modify the Mitchell bombers with the help of the talented people of the 4th Air Depot based at Townsville, New Guinea.

The first B-25Cs to receive extra firepower were equipped with two additional .50 caliber guns in the bomber’s nose to go along with the two already mounted there. As the modifications developed, the bombardier’s compartment was eliminated, and the glass nose was normally faired over.

Even with the B-25’s nose filled with AN/M2 aircraft guns, Colonel Gunn’s armorers dreamed up new ways to add forward-firing .50 caliber MGs. Streamlined gun pods containing a pair of .50 cal MGs were fabricated and installed on each side of the B-25 fuselage below the cockpit windows. The extreme vibration caused by the big MGs’ muzzle blast required that the metal fuselage skin be reinforced around the gun pods. Additional bracing was also placed between the fuselage and the engine nacelles to keep the wings from being damaged by the recoil forces of the .50 cal guns.

While the benefits of the B-25 gunships were quickly apparent, the USAAF supply of Browning AN/M2 .50-cal. MGs was sorely limited throughout the SW Pacific area. Consequently, the early days of the “strafers” saw Pappy Gunn and his crews scouring Australia and throughout the Solomon Islands for all the .50-caliber guns and ammunition they could beg, borrow or steal.

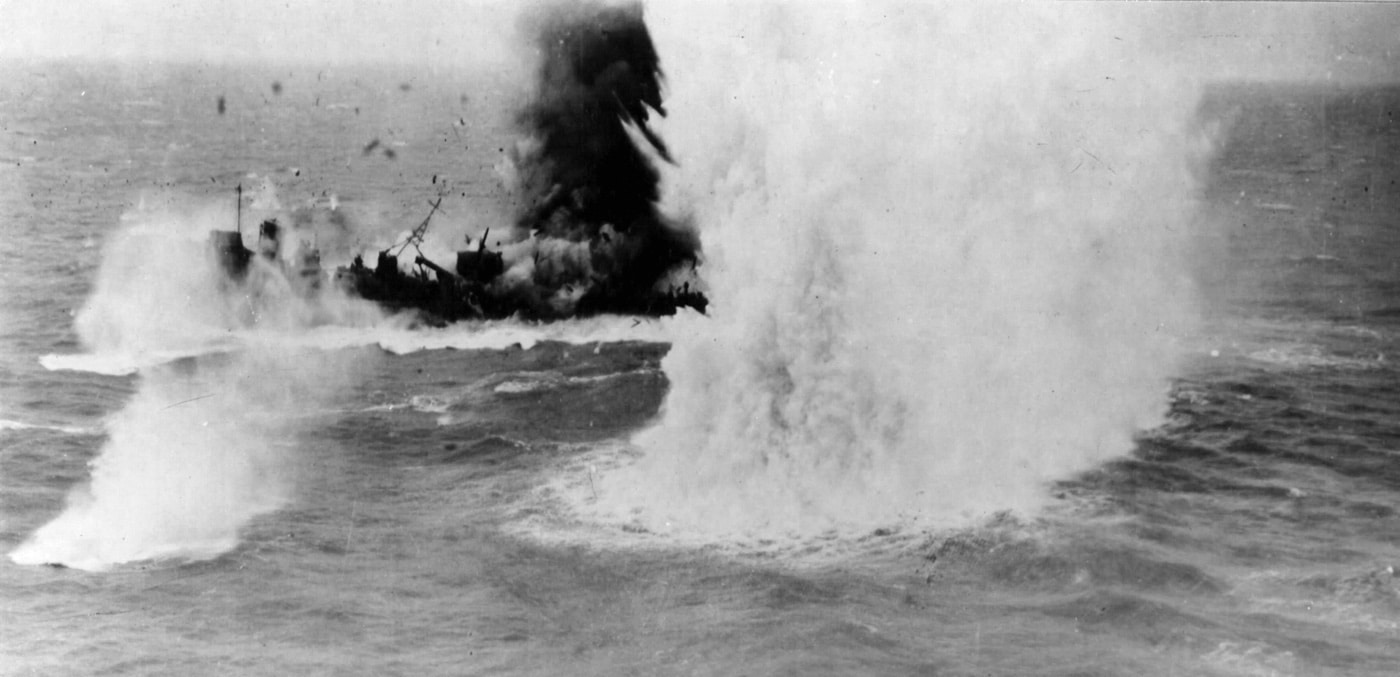

The modified B-25Cs and B-25Ds “strafers” of the 5th and 13th Air Forces quickly became a nightmare for Japanese forces. The gunships’ prime targets included Japanese coastal barges, supply ships, merchantmen and even their escorts — the .50 caliber armor-piercing slugs (fired at 850 rpm and travelling at 2,910 fps) blasted out the sides of all but the most heavily armored Japanese warships.

Ships that were not sunk by gunfire or skip-bombed to the bottom of the Pacific were left as smoldering hunks of Swiss cheese. Japanese supply convoys were strafed and skip-bombed to the bottom of the Pacific.

In airfield attacks, the B-25 gunships quickly defined the idea of flak suppression, crushing anti-aircraft defenses near aerodromes (and shipboard AA alike). The .50-caliber MGs tore through the lightly constructed Japanese aircraft, and the Mitchells left behind a trail of “parafrag bombs” floating gently down on small parachutes to explode over the parked airplanes and fuel dumps, showering them with fragments. Some of the parachute-slowed bombs contained phosphorus, setting fire to whatever the frags tore open.

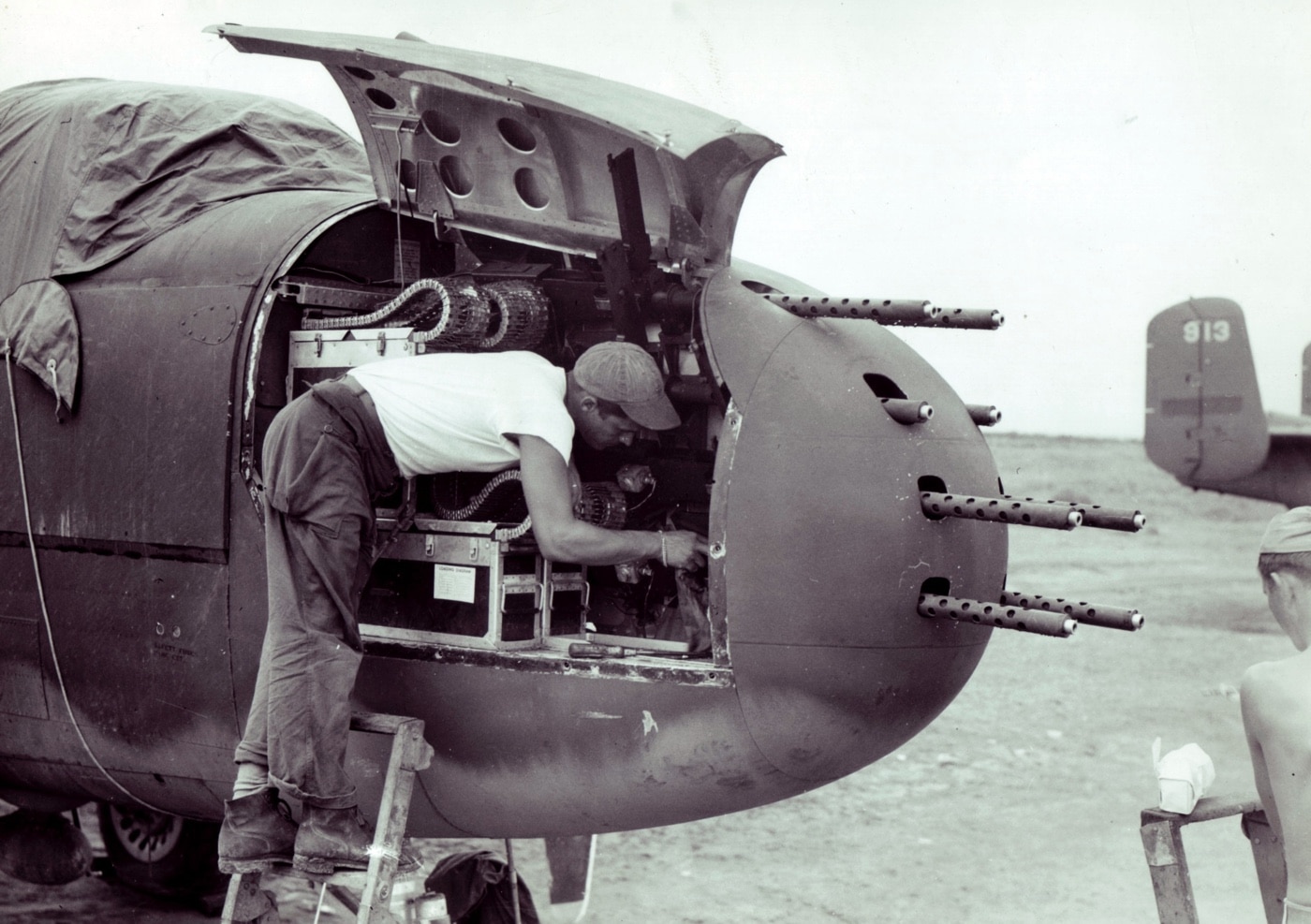

As the war progressed the folks at North American Aircraft developed a factory-designed B-25 gunship, culminating in the B-25J. The solid-nose B-25J carried up to a whopping eighteen .50 caliber MGs, with eight guns in the nose, four in fuselage side packages, two in the top turret, one in each waist position, and finally a pair in the tail gunner’s position.

However, the first 555 B-25Js were delivered without the cheek gun packages as the muzzle blast from the .50-caliber guns was found to buckle the fuselage plates. This was remedied by providing heavier gauge patches to reinforce the fuselage skin. Even though later production runs reinstated the cheek gun packages, crews normally removed them to save weight and overall stress on the airframe. It seems that even with the joys of .50-caliber firepower, you can have too much of a good thing.

.50-Cal. Firepower on the Mitchell

The .50 caliber (Aircraft, Caliber .50 AN/M2 Fixed) was a lighter version of the infantry M2 machine gun. Designed for use as a fixed or flexible gun for use in U.S. Army and U.S. Navy aircraft (hence the “AN” prefix), the AN/M2 also had a faster cyclic rate than the infantry gun (firing up to 850 rounds per minute). Mounted in a fixed position within the aircraft wings or fuselage, the AN/M2 was fired by remotely mounted solenoid trigger. When used as a “flexible gun” the AN/M2 used butterfly triggers. The lighter barrel of the AN/M2 was effectively cooled by the aircraft slipstream.

The .50 caliber machine guns used combinations of standard ball, armor-piercing (AP), armor-piercing incendiary (API), and armor-piercing incendiary tracer (APIT) rounds. The AN/M2 armor-piercing rounds could penetrate 20mm of armor plate at 500 yards. The API and APIT rounds created a flash and smoke on contact, and pilots observing strikes close to their targets often simply “walked” their fire into the bullseye.

In 1943, the M8 .50 caliber armor-piercing round was modified by adding a stronger incendiary component and an improved tracer compound. This became the highly effective M20 API round (adopted in June 1944), a 619-grain projectile blazing to its target at nearly 3,000 feet per second. Woe came to all things in its path.

Cannon-Packing B-25

Experiments in up-gunning the B-25 led to the concept of mounting a 75mm cannon in the nose. A jury-rigged 75mm field gun mounted in the crawlway of a B-25 proved that the aircraft could carry and fire the big gun while aloft, and these efforts led to the factory-designed B-25G cannon-carrying aircraft.

The M4 75mm cannon was 9 ½ feet long and weighed approximately 900 pounds (without ammunition). The mount included a special cradle that absorbed much of the tremendous recoil energy and the gun recoiled 21” on a rail extending under the pilot’s seat. Despite all the recoil-dampening efforts, the impact on the aircraft upon firing the 75mm was still quite severe, ranging from heavy vibration and shuddering to a split-second braking of the aircraft in flight.

The B-25G navigator became responsible for loading the 75mm cannon, and it was a rather difficult job hand-loading 15-pound shells in a tight space inside a pitching and rolling aircraft. Storage for 21 rounds of 75mm ammunition was standard. The pilot aimed the 75mm gun by using the twin .50-caliber machine guns in the nose to put a burst of tracers into the target to adjust his aim. Accuracy for the cannon was considered acceptable, and the 75mm gun was certainly more accurate than unguided rockets launched from underneath the wings.

However, as it was hand-loaded, the cannon was very slow firing, and this caused the attacking B-25 to be vulnerable to AA fire as the bomber would have to hold steady on its attack run. The impact of the 75mm rounds was devastating though, and Japanese barges and light coastal craft were favorite targets to blast into tiny bits. Ultimately, the massed firepower from .50 caliber MGs proved more effective than the cannon, and many of the B-25 cannon ships removed their 75mm guns in favor of a pair of .50-caliber MGs.

Like other WWII aircraft fitted with heavy cannon armament (notably the British Mosquito FB MKXVIII with a 57mm gun, the German Hs129 B-3 with a 75mm Pak 40 cannon, and the German Ju88P-1 with a 75mm Pak 40 cannon), the cannon-armed B-25s were an oddity with great tactical limitations. Its performance was acceptable, but ultimately there were better solutions available. In the end, the cannon-armed B-25G/Hs were used exclusively in the SW Pacific and in the China-Burma-India theatres of operation.

Conclusion

Other American bombers were configured as gunships: the Douglas A-20, a twin-engine light bomber carried up to six .50-caliber MGs in its nose. The later Douglas A-26B carried up to eight .50-cal. guns in a “solid” nose package. The A-26 (later designated B-26 in 1947) continued the gunship tradition, serving in the Korean War and then in the Vietnam War. Clearly, the B-25 gunship represented a formula that worked, and one that carries through to the AC-130 of today!

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

772

772