When Japanese Balloon Bombs Struck America

June 1st, 2023

8 minute read

It was Monday, May 7, 1945, and the headline of the Klamath Falls, Oregon Herald and News read: “Blast Kills 6, five children, Pastor’s wife in explosion”. The indiscriminate violence of World War II had come to America, and it was delivered by an unlikely source.

On Gearhart Mountain in Oregon, a 15-kilogram anti-personnel bomb had exploded in the midst of a group of children on a fishing trip with their local pastor and his wife: Edward Engen (13), Jay Gifford (13), Sherman Shoemaker (11), Joan Patzke (13), and Dick Patzke (14) were killed, along with Mrs. Elyse Mitchell (26). The Reverend Archie Mitchell was in his car talking to a group of Forest Service employees working on the rough mountain road — trying to find if the route was passable and if the fishing prospects were good. His wife and the children excitedly called from the tree line about a hundred yards away: “Look what we found!”

Seconds later the bomb attached to the balloon apparatus exploded among them. The children were killed instantly. Mrs. Mitchell, her clothes set on fire, lived for just a few minutes. The workmen ran to the scene and were horrified by the carnage, and no one knew what caused the explosion.

The tragedy on Gearhart Mountain was the terrible and deadly exception to Japan’s strange “balloon bomb offensive” against the United States. By the grace of God, no other Americans were injured by the more than 9,000 balloon weapons launched against America.

Japan’s Vengeance Weapon

After Japanese fortunes had turned sour in their Pacific war against America, the Emperor’s military planners looked for a way to strike the United States in a meaningful way. In late 1944, the U.S. Army Air Forces stepped up the pressure on Japan with an increasing amount of bombing raids with B-29 Superfortress bombers. Early B-29 raids originated from bases in China, and then transitioned to newly won airfields in the Marianas Islands. The Japanese had no such long range bombers and were thought to be otherwise stymied in their efforts to reach the continental USA. Even so, their motivation to strike back was high.

A balloon may seem to be a strange choice for an intercontinental weapon, but the Japanese discovered a natural phenomenon that could assist them in attacking America from afar. The Japanese combined weapons technology with meteorology by floating bomb-carrying balloons into the existing high-altitude air currents, and letting the wind carry the simple weapon across the great expanse of the Pacific. Today, we call those winds “the jet stream”, but in the fall of 1944, one of Mother Nature’s little secrets propelled the world’s first intercontinental weapons system. Since the balloon bombs were unguided, the Japanese reckoned their best use would be to start forest fires in the American Northwest and the length of California — causing casualties whenever possible, and if all went to plan, tying up considerable manpower resources to fight the resulting fires.

Fu-Go: Balloon Bombs

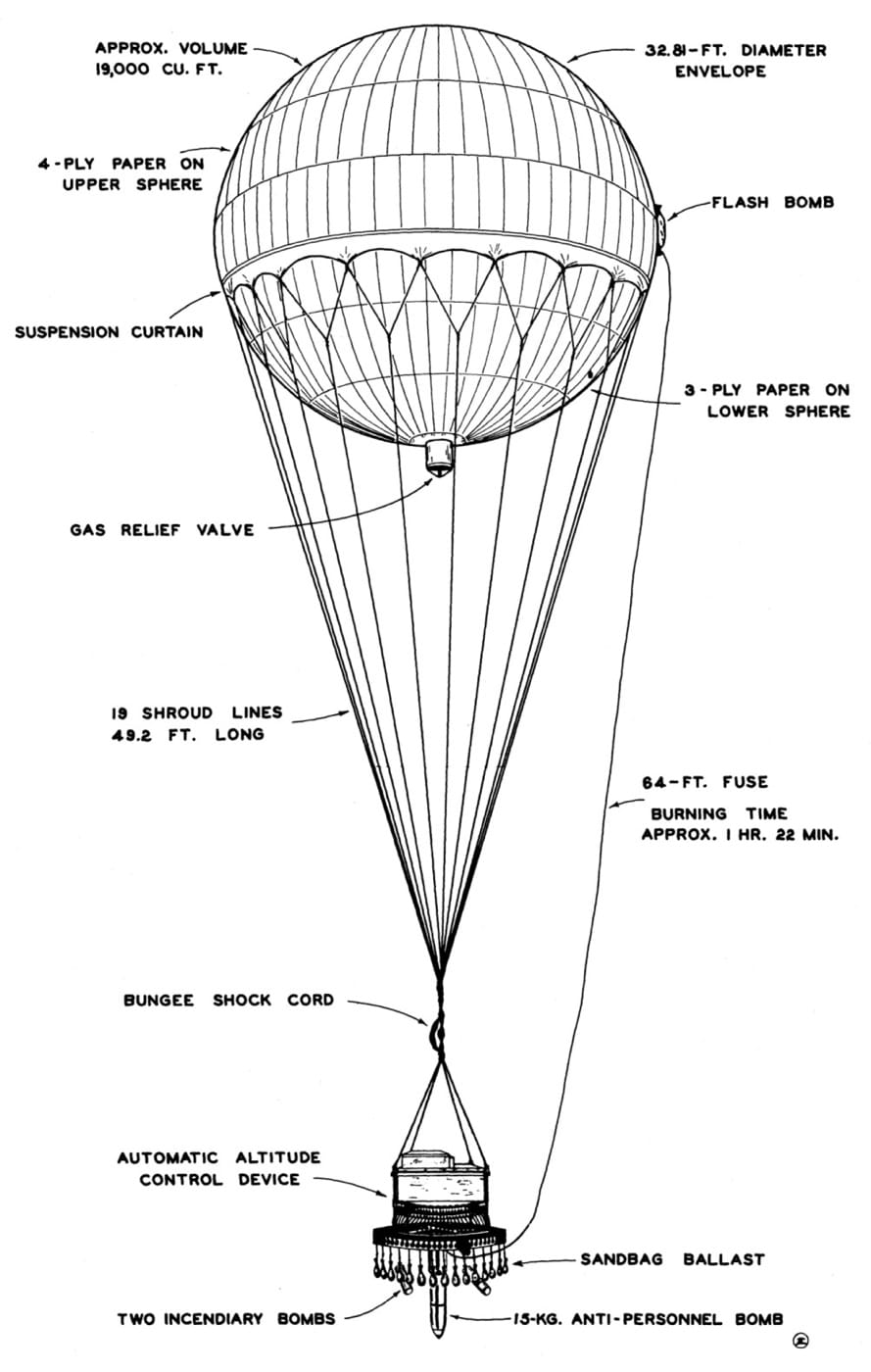

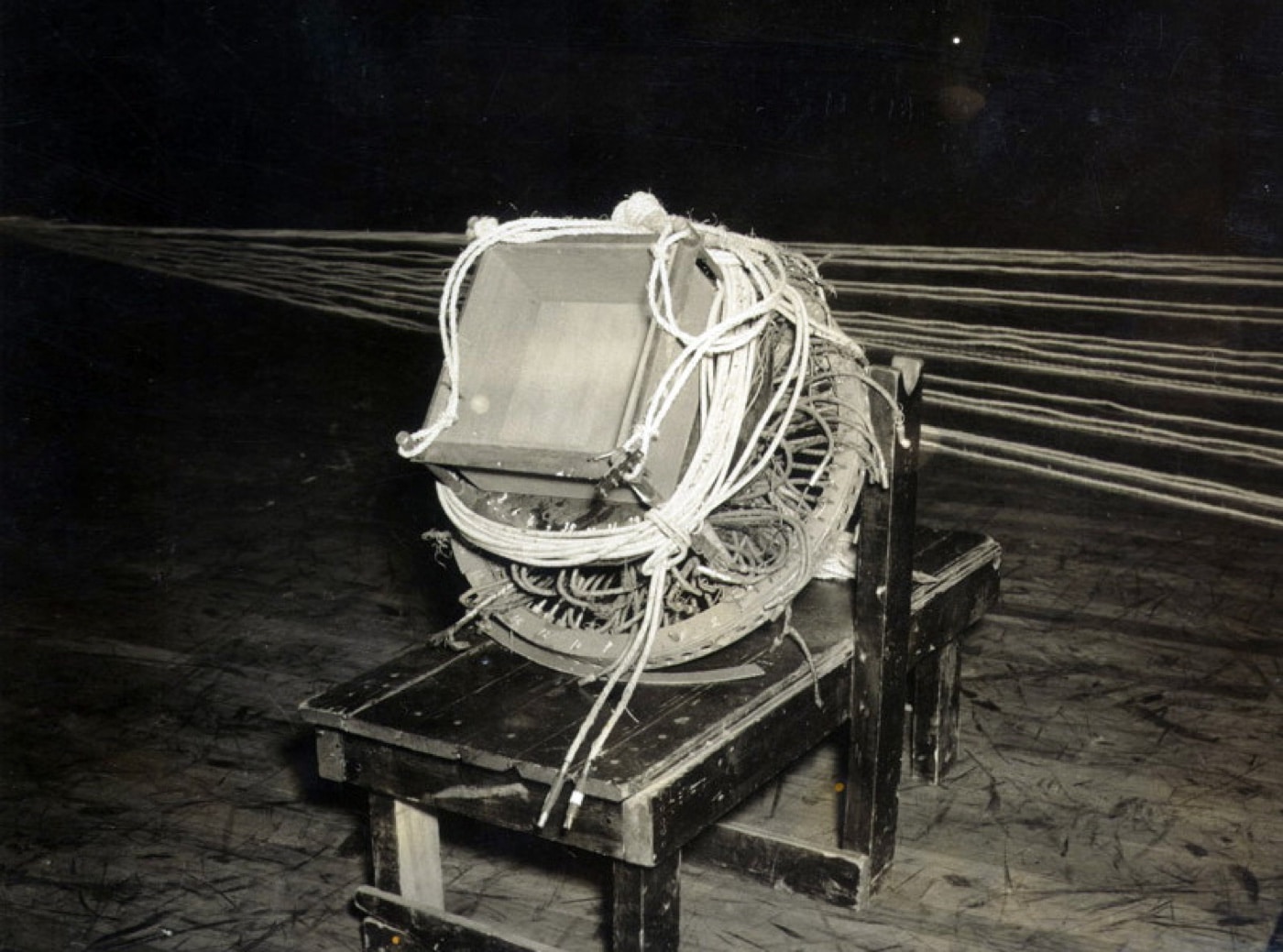

The Japanese made the balloons from mulberry paper and filled them with hydrogen. Called “Fu-Go”, they measured 33 feet in diameter and could carry a payload of four 11-lb. incendiary bombs, along with a 33-lb. anti-personnel bomb. Some Fu-Go carried a single 26-lb. incendiary bomb. The balloons used a relatively sophisticated altitude control mechanism (based around an altimeter), releasing hydrogen if they climbed above 38,000 feet, or dropping pairs of ballast bags if they fell below 30,000 feet. Balloons were expected to rise in the daytime heat and then fall a bit in the cool of the evening. Once over the target of the Continental USA, the balloon would finally come down to ultimately blow up.

Beginning on November 3, 1944, and concluding in late April 1945, the Imperial Japanese Army sent up approximately 9,300 balloons from 21 specially developed launch stations. Three balloon battalions were created, and their combined launching capacity was about 200 launches per day (depending on the weather). A few balloons in each group carried radio tracking equipment to estimate their progress toward North America. Japanese planners estimated that only 10 percent of the balloons would reach the United States. U.S. wartime analysis described that approximately 300 Fu-Go balloons were found in America and Canada, plus a few in Mexico. Several Fu-Go came down as far to the east as Michigan.

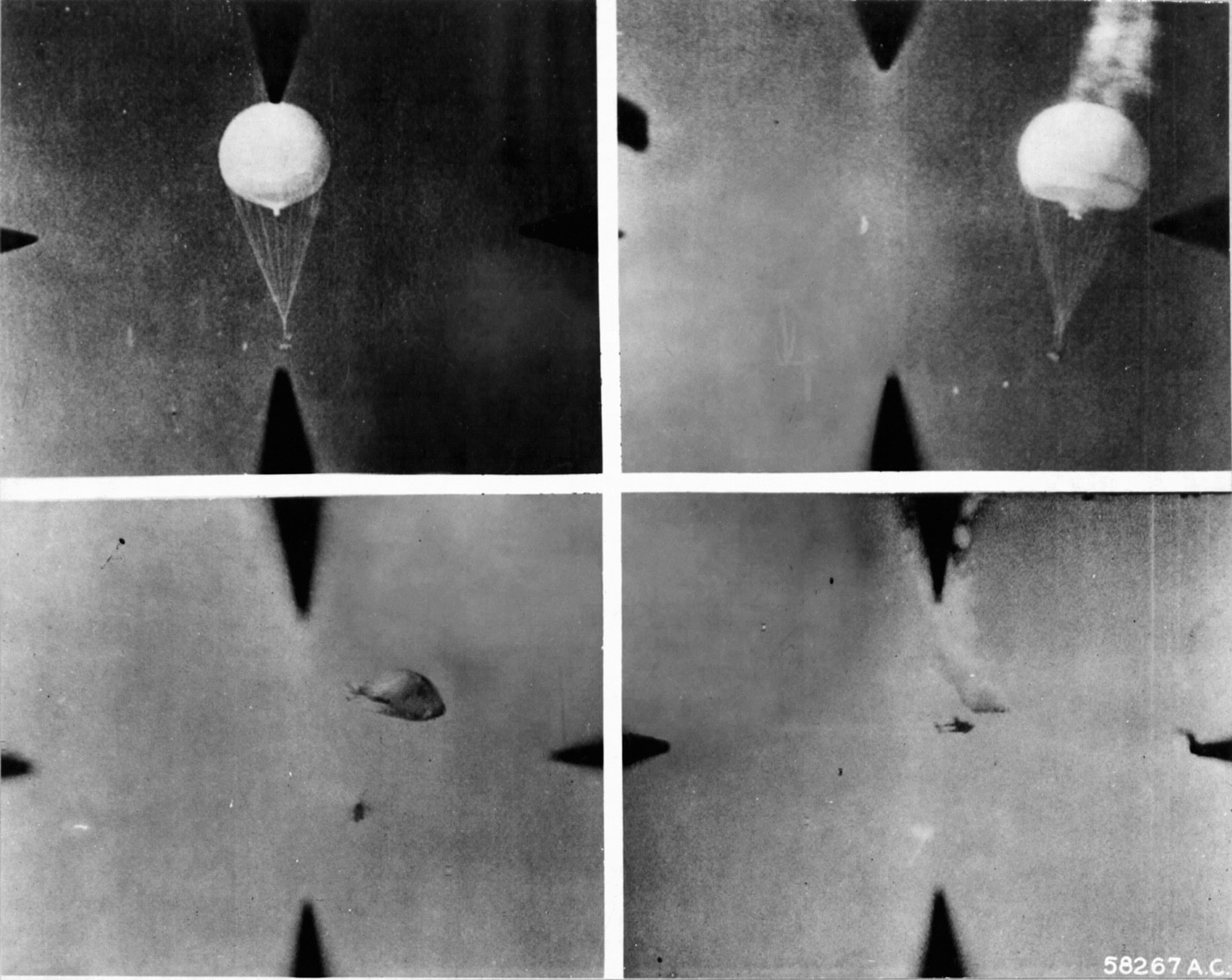

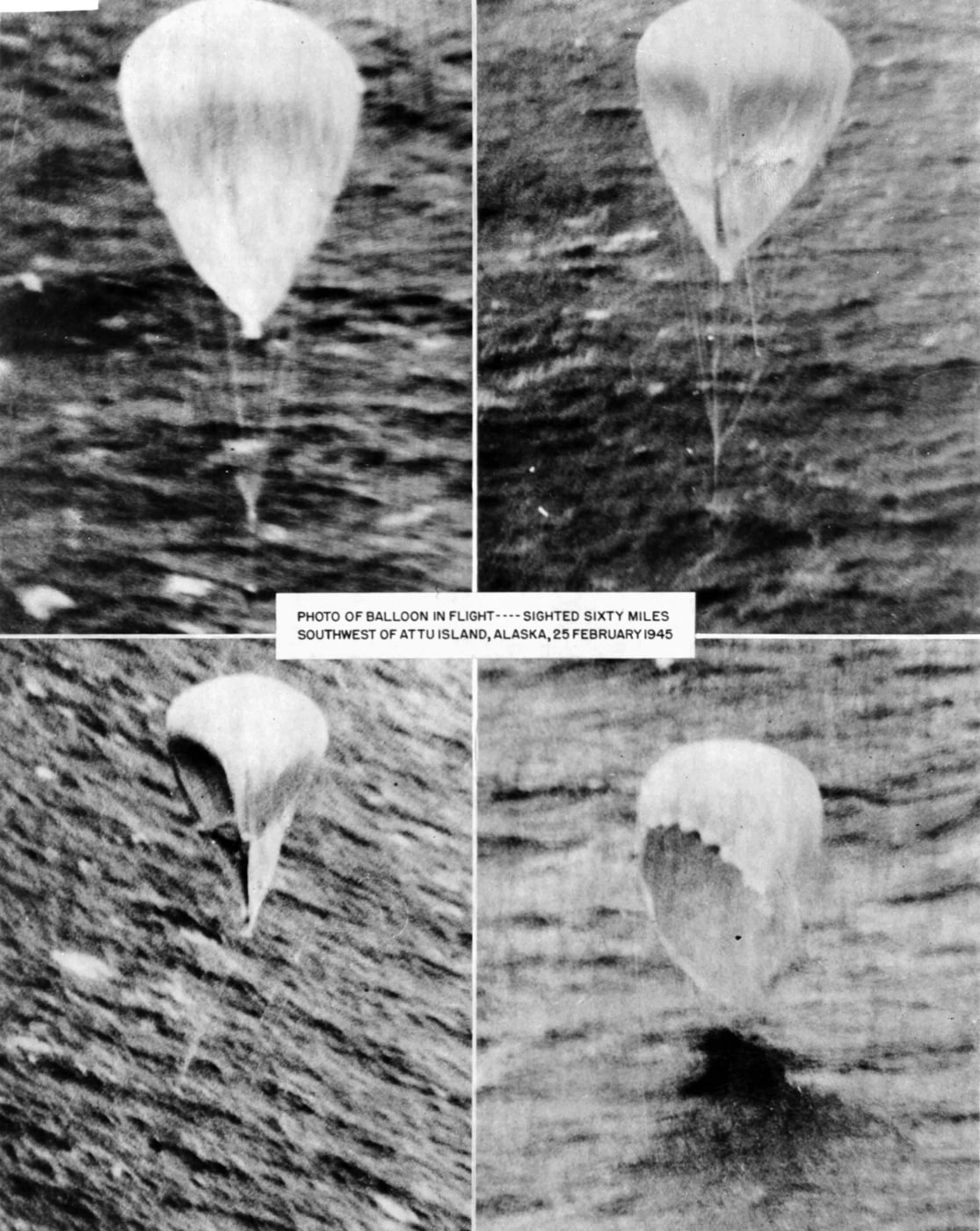

During July 1945, the U.S. Military finally released information about the Japanese balloon bombs, coupled with gun camera footage from intercepting P-38 Lightning fighters based on Attu in the Aleutian Island chain. The following description of the balloon bombs is a transcription of the narration over the short film featured in Combat Bulletin:

For the past several months, since 10th March, long range free balloons, released in Japan, carried explosives to the North American continent. Easterly winds that prevail at 20 to 30 thousand feet swept the balloons across the Pacific in 85 to 135 hours. Aleutian-based fighters intercepted a number of the balloons and made photographic passes before shooting them down. About 33 feet in diameter, the balloons were filled with 19,000 cubic feet of hydrogen gas. Ballast dropping mechanisms and bomb loads were hung about 45 feet below the bag. When hit with incendiaries, the balloons burned but did not explode. A detonating charge and flash bomb were supposed to destroy the apparatus when the balloons mission was completed — but a number of them were found intact. The spherical bag was made of five-ply rice paper, which was shellacked for weatherproofing. Construction indicated the balloons were being mass-produced at little cost. An escape valve automatically released gas if the balloon rose too high. Anti-personnel and incendiary bombs and the control mechanism were mounted on a circular aluminum frame — ballast was automatically released when the balloon dropped below a set altitude (which is estimated to be 20,000 feet). A wet cell battery was carried to power the operations of the control apparatus. Ballast weights were held by simple hooks. A series of barometric aneroid switches governed height. It is believed the main purpose of the bombs was to start brush and forest fires, but the attacks were so scattered and aimless that they posed no military threat.

Information Suppression, Sinister Suspicions

U.S. officials discovered a Fu-Go balloon for the first time in early November 1944. Within a few weeks several more had been found from Alaska to California and in Montana, Wyoming, and Oregon. National and state agencies were alerted, and forest rangers began to actively search for evidence of balloons. Once the U.S. military was convinced that the balloons had originated in Japan and that America was under attack from this strangely silent weapon, the Office of Censorship was involved.

Beginning on January 4, 1945, newspapers and radio stations were requested (strongly encouraged, guilted, or sometimes threatened) to suppress any reporting of balloon incidents. The censorship strategy was designed to (1) keep Japanese agents in North America in the dark, and (2) prevent panic among American citizens. This censorship proved effective, and few Americans even today have even heard of the balloon bombs. Japanese propaganda began reporting massive fires and widespread panic in the western USA, but no one paid any attention.

U.S. officials also worried about a far more deadly use for the balloon bombs — namely chemical or biological warfare payloads. Japan had already used biological and chemical weapons against Chinese forces in the Battle of Changde during 1943, and there was a credible threat that they would use them against the United States. Postwar evidence shows that Japanese bio-chem warfare proponents wanted to use bubonic plague, anthrax, rinderpest, and smut fungus to attack America. Prime Minister Tojo refused to approve this type of attack, as he believed that the U.S. would respond in kind with overwhelming force.

In early 1945, U.S. officials initiated the “Lightning Project” by directing agricultural officers and veterinarians to look for evidence of any new types of livestock or crop diseases. Decontamination chemicals and gear were stockpiled in the West, and realistic preparations were made to deal with biological warfare that thankfully never came to pass.

Operation Firefly

While keeping news of the balloon bomb attacks out of the media, the U.S. military created a secret operation to combat the growing number forest fires started by Japanese incendiaries. The program was titled Operation Firefly, and this mobilized the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, America’s first black paratrooper unit.

The men of the “Triple Nickels” thought they were being sent to the Pacific Theatre but instead found themselves stationed at Pendleton Field in Oregon. There they trained for their dangerous new mission — parachuting into remote areas of the northwest to fight fires.

Ultimately, the men of the 555th fought 28 fires between July and October 1945, parachuting in to combat 15 of them. One member of the 555th died during a jump in early August — fortunately he was the only fatality of Operation Firefly.

During this time, the term “Smokejumpers” was created and often used to describe the airborne firefighters. But since the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion was a U.S. Army unit, they were described in official reports as paratroopers, serving their nation during wartime when it was attacked by a foreign power.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

545

545