When Eisenhower Sent the Marines to Beirut

August 5th, 2025

16 minute read

Editor’s Note: For many readers, a peacekeeping force of U.S. Marines in Beirut reminds them of the deployment in the early 1980s and the horrific suicide bombing in ’83. However, this was not the first time America sent men into harms way in an effort to bring stability to the region. In today’s article, we look at an earlier intervention, the 1958 Lebanon Crisis, that began roughly 25 years prior.

That’s the thing about the Marine Corps. You deploy aboard one of the Navy’s haze-grey hotels, and you just never know what will happen next. There you are on a leisurely cruise through the Mediterranean one day, and the next day you’re armed up and making a landing at some place you probably couldn’t find on a map.

Something like that was probably crossing the minds of Marines from the Battalion Landing Teams on patrol in the Med in the summer of 1958. Senior officers were well aware of trouble in the Levant, a Middle East hotbed rumbling with political problems in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. Down in the ranks, it was mostly boring business as usual with Marines and sailors looking forward to liberty in Malta, Crete and other Western Mediterranean ports.

Meanwhile, in Washington, President Dwight Eisenhower was meeting with political and military advisors and pondering a serious situation in the countries of the Middle East that featured vast oilfields and pipelines that were of vital importance to the economy and military power of virtually all Western nations. There had been violent upheaval in Iraq. The Iraqi king had been assassinated in a military coup and that caused shock waves throughout the region. Suddenly, the Iraq-Jordan confederation was shaky, there was potential for a union of anti-western forces in Egypt and Syria, and in Lebanon, factional disputes led that nation’s leaders to fear a civil war between Lebanese Christians and Muslims in the divided but generally peaceful nation.

Serious amounts of defecation were nearing the oscillation and President Eisenhower had to decide how to respond to a call for intervention from Lebanese President Camille Chamoun who had been desperately trying to broker peace amid the turbulence surrounding his country. The situation in Lebanon was turning sour quickly. Strikes and disorders were threatening from Tripoli south to Sidon and all along Lebanon’s coast. Insurgents were reportedly streaming into the country from Syria through the contiguous Bekaa Valley. Lebanon’s senior military commander General Fuad Chehab feared a violent clash between Christian and Muslim factions of his armed forces. With violent conflict on the horizon, Lebanon needed some kind of serious intervention featuring a military powerful enough to intimidate warring parties.

And that would involve two Marine Battalion Landing Teams steaming through the Med in a series of exercises with the US 6th Fleet. Watching the dispatches from the State Department and wisely anticipating action in Lebanon, the Fleet Marine Force Atlantic cobbled together a 2nd Provisional Marine Brigade consisting of BLT 2/2 (2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines), and BLT 3/6 (3rd Battalion, 6th Marines), both currently at sea from home station at Camp Lejeune, NC. The call to land the landing force came on 15 July and kicked off the operation.

Operation Blue Bat

In hasty pre-landing briefings, the Marines were simply told the mission was to support the legal Lebanese government against any foreign invasion. The major threat was thought to be the Syrian First Army (40,000 troops supported by Soviet supplied T-34 tanks) located between Damascus and the Israeli border, which put them just a few hours road march from Beirut.

The initial directive from Washington called for Marines to land over Red Beach near Beirut International Airport (BIA) and implement as much of a larger intervention plan as possible once ashore in Lebanon. That called for landing two Marine BLTs, one coming ashore northeast of Beirut to secure the water supply systems, bridges, and the northeastern sector of the city. The other BLT would strike across the beaches south of Beirut to seize the airport. As soon as the Marines had established control of the airport, a British infantry brigade would be flown in from Cyprus. When the Brits arrived at BIA, the Marines would push deeper into the city and gain control of the port.

Beyond the looming Syrian threat, the internal situation in Lebanon seemed equally grim. By mid-July 1958, anti-government rebels in Lebanon numbered about 10,000, dispersed in bands of 400 to 2,000 lightly armed men. There was no central leadership of the rebel forces; each group was loyal only to an individual leader. The Americans did not expect any reaction from the regular Lebanese Army, though the danger existed that it could disintegrate into pro-government versus rebellious factions. All that was being closely watched as the Marines came ashore.

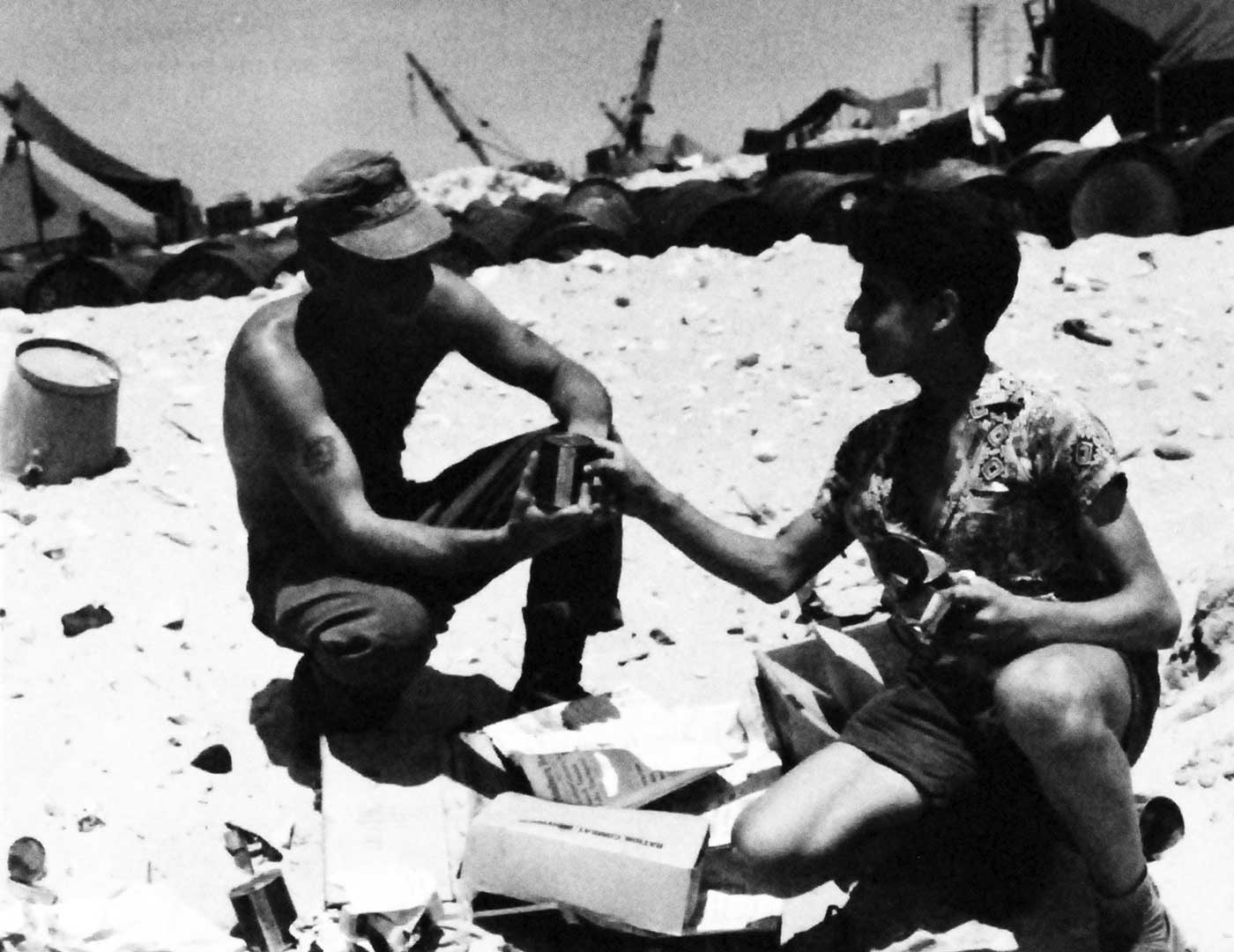

The landings via amphibian tractors and Navy LCIs were anticlimactic. What Marines encountered at Khalde (Red) Beach, some four miles from downtown Beirut and just 700 meters from BIA, were villagers going peacefully about their chores and bikini-clad vacationers soaking up the sun on a summer afternoon. That was unexpected, as Marine leaders had been told about a boastful rebel leader in Beirut named Saeb Salem who sent a message to the U.S. ambassador. “You tell those Marines that if they set one foot on the soil of my country, I will regard it as an act of aggression and commit my forces against them.”

The Marines laughed it off as they moved to their initial objectives, but General Chehab was sweating bullets. He feared the American intervention would bring about dissolution in the ranks of his army. A group of senior Lebanese soldiers had informed him of a planned coup to prevent the landings. The General was on shaky ground and said he could not guarantee the loyalty of his forces. A message warning of this situation never reached the ships of Amphibious Squadron 6 then steaming offshore, so the landings went ahead as planned.

As Echo Company 2/2 cleared the civilians from the beach, Golf Company secured the airport terminal, while Foxtrot and Hotel Companies began to establish positions around the airfield. No incidents took place and no shots were fired. The only sketchy incident took place when President Chamoun, reacting to reports that he was to be assassinated at midday, requested Marine protection. After pledges of loyalty from his subordinates, General Chehab quashed that request and guaranteed that the president would be guarded by Lebanese Army troops.

Solidifying a Foothold

The Marines turned their attention to shoring up the supply situation and improving their logistics pipeline from ships offshore. It was a tough slog as Red Beach presented problems with an offshore sandbar and slick, shifting sands. The ideal landing vessel, USS Plymouth Rock (LSD-29), the LSD committed to BLT 2/2 and carrying much of the landing force support equipment, was stuck at Malta undergoing repairs. Marines and sailors improvised, manhandling supplies from shallow-draft landing craft onto the beach in an all-night effort.

The Marine Corps’ rugged M-274 mechanic mules played a pivotal role in getting vital supplies ashore and into the hands of the BLTs now digging in for an extended stay in Beirut. When the USS Fort Snelling (LSD-30), an LSD assigned to support BLT 3/6 arrived with necessary landing equipment, the situation improved and, by nightfall on 15 July, three tanks and a fleet of trucks were ashore and ready for action.

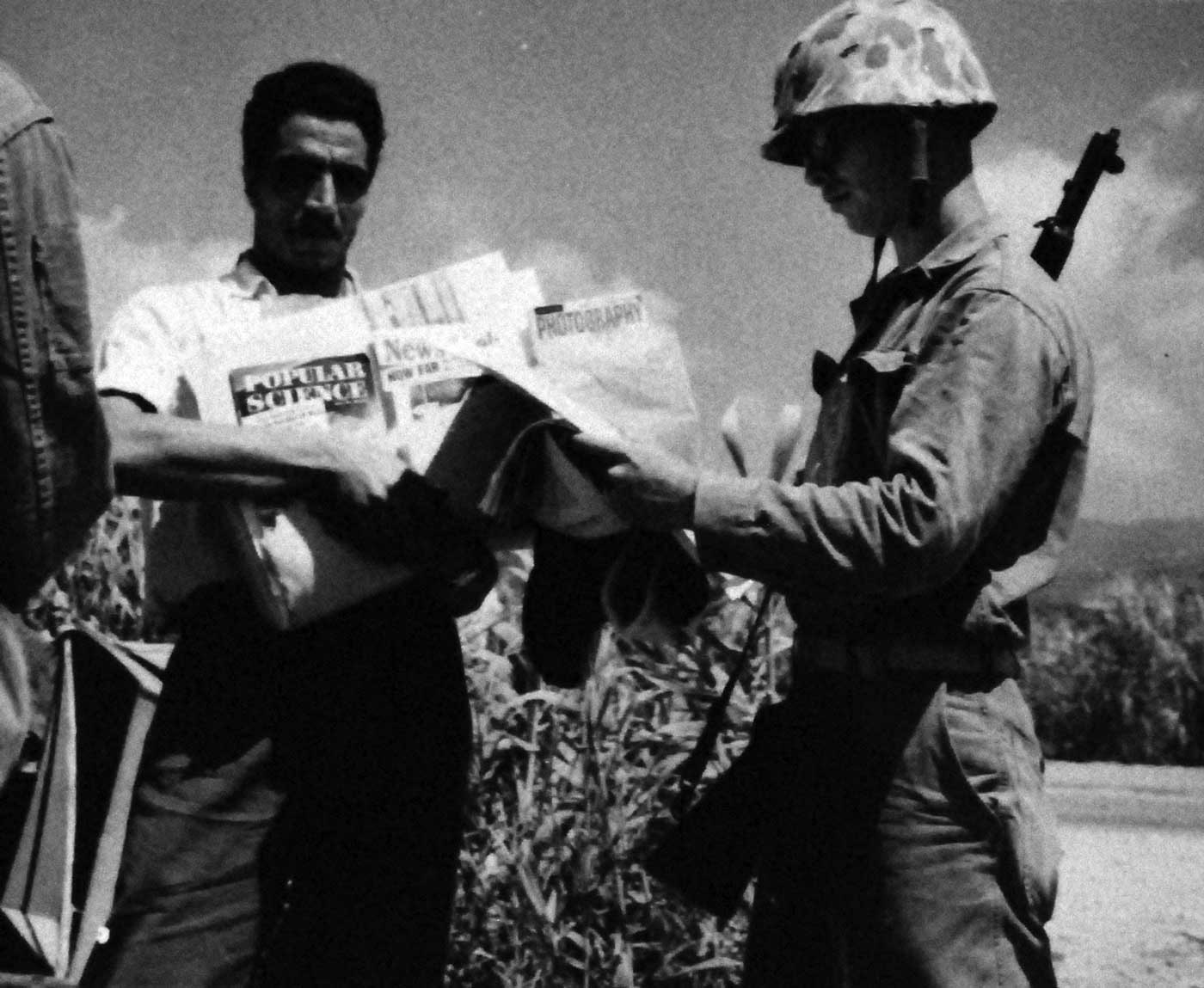

As supplies were being unloaded onto the beach, BLT 2/2 Marines at the airport were consolidating their positions. A defense perimeter had been adjusted to address likely threats and liaison was made with Lebanese units at the airport where certain some areas were guarded jointly by Marines and Lebanese airport police. Commercial air traffic was scanty but allowed to land and depart from BIA. A motorized platoon from Echo Company 2/2 was on standby to push into Beirut proper if American, French or British Embassies were threatened.

The Next Step

The next day at 0730, with their support ships fully assembled offshore, BLT 3/6 landed across the sands at Red Beach to relieve BLT 2/2 at the airport. Orders directed 2/2 to push on into downtown Beirut with objective of reaching the port facilities. With a convoy of tanks, AMTRACs and trucks fully loaded, 2/2 pushed toward the city until they ran into a Lebanese Army roadblock. The standoff was getting dicey and lasted for some tense hours while a brass-laden contingent of Naval officers, Marines, Lebanese soldiers and diplomats scurried back and forth, shouting into phones and at each other, until a face-saving agreement was reached.

Admiral James L. Holloway Jr., commander of Naval Forces in the Atlantic and Mediterranean who was on hand exercising overall command, arrived at the flashpoint. Assisted by another admiral as well as a Marine Brigadier General, Holloway personally led the 2/2 convoy into Beirut dock areas. The Marines took control of the port and guarded bridges over the Beirut River via the Tripoli Road. The kerfuffle was typical and demonstrated the Marines’ take on their mission in Lebanon. They were to be polite and cooperative but firm. It played out mostly that way all day every day as Marine patrols ran into Lebanese Army roadblocks.

What Happened to the British Army Support?

What about that British Army brigade that was supposed to land in Beirut as soon as the Marines had secured the airport? Seems that part of the plan was scrubbed by the British MOD before it could be implemented. Three days earlier, while Marines were still flowing ashore in Lebanon trying to deconflict a sticky situation, British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan opted out of the Beirut commitment to land paratroops in Jordan at the request of King Hussein.

As usual in the turbulent Middle East, things were getting increasingly complicated. The planned British role in Lebanon would now be assumed by the Europe based US Army 24th Airborne Brigade. In Beirut, it was getting to the point where you couldn’t tell the players without a scorecard. At 0900 on 18 July, a third battalion of the 2nd Provisional Marine Brigade was added to the mix when BLT 1/8, extended in the Med while they were homeward bound, came ashore at Yellow Beach, four miles north of Beirut. They promptly fanned out in a crescent-shaped perimeter to guard the beachhead to the south and secure northern approaches to city. The only problems encountered in that landing were posed by the usual congregation of Lebanese spectators and ice cream and watermelon vendors.

The Rest of the Team

The U.S. Army command in Europe dusted off its plan for emergency commitment to the Middle East and created a task force consisting of two airborne battle groups divided into five elements and designed for deployment as a whole or piecemeal depending on requirements. Their Task Force Alpha (187th Infantry) including the battle group command element was airlifted from Bavaria to Beirut on 19 July.

That move involved U.S. Air Force elements in a relatively massive transport lift from Europe to the Middle East plus fighter escorts. The U.S.A.F. scrambled elements from all over the globe to get it done working from a borrowed base at Adana, Turkey. Very shortly, the Air Force had some star-wearing players in the game and command and control was becoming truly complicated. The Navy and Marine Corps were already there, the Army with a large combat command was on the way, and the Air Force was claiming control of the air spaces over Lebanon.

Meanwhile, the Marines were doubling down on their commitment. A decision had been made to reinforce the three BLTs committed to the 2nd Provisional Marine Brigade in Lebanon with another battalion from Camp Lejeune. The 2d Battalion, 8th Marines, were on their way in what passed in those days as a massive airlift. It took 12 aging propeller-driven R5D aircraft, the Navy’s version of the Douglas C-54 Skymaster, from the west coast plus 14 R4Qs (think C-47 Skytrains) from east coast bases making refueling stops in Argentia, Newfoundland and at Lajes in the Azores to move 800 Marines from the US to Port Lyautey, Morocco. From there, Marine aircraft departed every 30 minutes heading for Beirut. The first lift of 2/8 Marines landed at BIA on the morning of 18 July and the battalion took up positions to the rear of BLT 3/6.

Despite American claims of neutrality, the Lebanese population and particularly the religiously divided Lebanese Armed Forces, didn’t really know what to think. They were looking at four full U.S. Marine battalions ashore in their country virtually controlling all major commercial arteries around Beirut. And a major U.S. Army contingent was inbound. Call it what you like, but it was looking increasingly like an armed invasion of Lebanon. Some saw it as an insult, an indication that the Lebanese government and their armed forces couldn’t deal with the problems at hand. Beirut was still a potential powder keg and its population was mushrooming with everything except native Lebanese.

Admiral Holloway reassured Washington that things were going well in Lebanon. In a cable on 19 July, he urged patience: “The moment may come when this is reversed but at present, patience, consolidation of strength, acclimating the Lebanese to our presence, and restraint that characterized our actions accompanied by our great potential military strength are paying dividends.”

Developing Issues

Despite Admiral Holloway’s reassurances, the command structure was about to become more complicated. Holloway had other command responsibilities and the most pressing issue locally was a senior officer to command all the troops ashore in Lebanon. It would require a tactful, deft hand and at least a two or three star officer given the growing troop commitment. As the U.S. Army troops landed on 19 July and deployed to reserve positions in an olive grove east of the airport, Marine Brigadier General Sidney Wade was the 6th Fleet landing force commander. The Marines expected one of their own two or three stars to take overall command of U.S. forces in Lebanon. The Joint Chiefs of Staff had other ideas.

To coordinate activities of the Army and Marine forces ashore, Washington decided that the best bet was a soldier. Citing the potential for U.S. Army forces to rapidly outnumber the Marines in Lebanon, on 23 July they appointed Army Major General Paul Adams as Commander in Chief, American Land Forces in Lebanon. Adams arrived in Beirut the following day. If there was any heartburn among the Marines, it wasn’t immediately obvious. They had more pressing problems.

Throughout July, the Marines experienced regular harassing fire from rebel factions directed at their forward positions. That got serious near the airport when rebels began firing at American aircraft flying into or out of BIA. Shots came from an area just south of the airfield, an area patrolled by BLT 3/6. Marines were sent out to find and dispatch the snipers and got involved in a three-sided firefight with rebels and Lebanese police dressed in civilian clothes. Rounds flew hot and heavy in several directions until a Lebanese Army unit arrived and sorted out the situation. The blame game went on for a while but the rebel harassing fire ceased and aircraft operated safely in the aftermath.

As a result of the airport battle and several other potentially explosive incidents, arrangements were made between General Chehab and American commanders to emplace Lebanese Army forces between U. S. and rebel positions in order to prevent clashes between the two. It was an odd way of doing business for American forces who were now asked to negotiate for positions rather than simply seizing them. Americans, particularly the Marines, didn’t much like static positions anyway, so General Wade got permission to begin motorized patrols. BLT 1/8 started by running reconnaissance patrols up to 20 miles east of their static positions north of the city.

On the Move

Each patrol involved a reinforced rifle platoon, with air and artillery observers along with Lebanese Army soldiers acting as interpreters and guides. Marine helicopters from the ships offshore flew surveillance along the roads looking for trouble ahead of the truck and jeep patrol vehicles. The patrols met no resistance and received an extremely friendly reception from the rural populace.

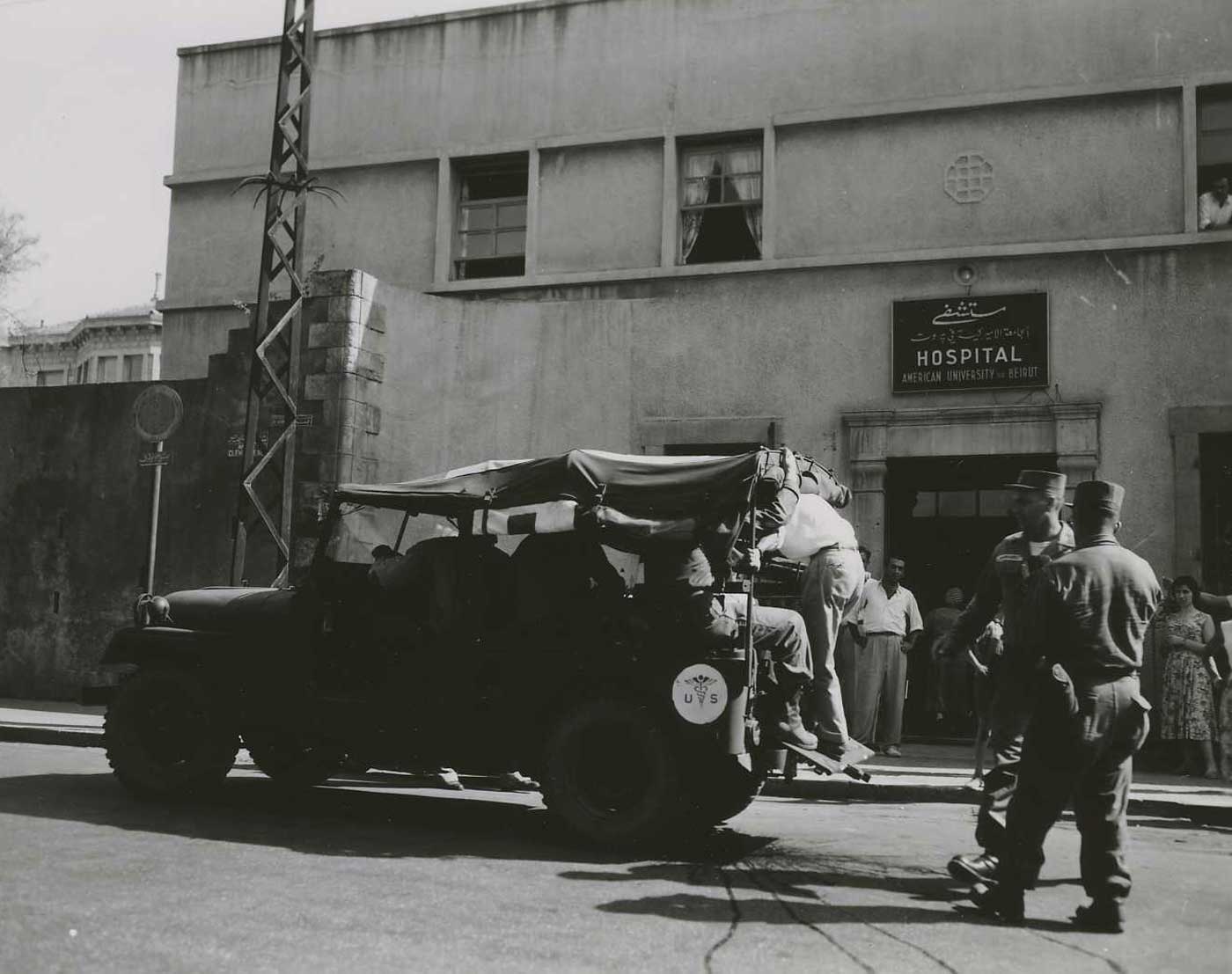

Meanwhile, the Army’s 24th Airborne Brigade was swarming into Beirut. New arrivals included tanks, artillery, engineers and a full-scale field hospital. It was getting crowded and some adjustments needed to be made to the disposition of Army and Marine forces. It was a circus for a while. The Marines of 2/8 who had landed in Lebanon on 23 July relieved BLT 2/2 guarding the dock area and key installations in the city. Most of BLT 2/2, the first Marines to land in Lebanon, set up a perimeter at J’deidah just under two miles east of Beirut. Under strict orders to avoid offensive contact with rebels, each redeploying unit made contact with Lebanese civil authorities as local liaisons.

Near the end of July, the Army battle group relieved BLT 3/6 at BIA. Army troops then assumed responsibility for the southern sector of the American defense perimeter, which included the airport, the high ground to the south, and Red Beach. BLT 3/6 redeployed through Beirut to the southern flank of 1/8 north of the city. By the end of July, the Army and Marines had consolidated to defend a perimeter extending 20 miles and guarding the city from attack in any direction.

As political ramifications of the American presence in Lebanon were being worked out at diplomatic levels, Army and Marine forces settled into a routine of housekeeping and local patrols.

Trading Off

Lebanon in the summer of 1958 was rapidly turning into an all-Army show of force. To support the effort, the Army brought in the entire 3rd Medium Tank Battalion (72 medium tanks and 17 APCs) from Germany. It seemed like massive overkill given the situation, but the American command was bound and determined to intimidate local rebels or outside insurgents. It appeared to be sound strategy. While insurgents continued to take potshots at Americans, the only two Marine deaths were caused by confusion and friendly fire. The Army lost only one man killed and one seriously wounded by rebel fire. So, it went in Lebanon throughout the summer. American forces were in the difficult position of being shot at while under orders not to shoot back unless they had a clear target.

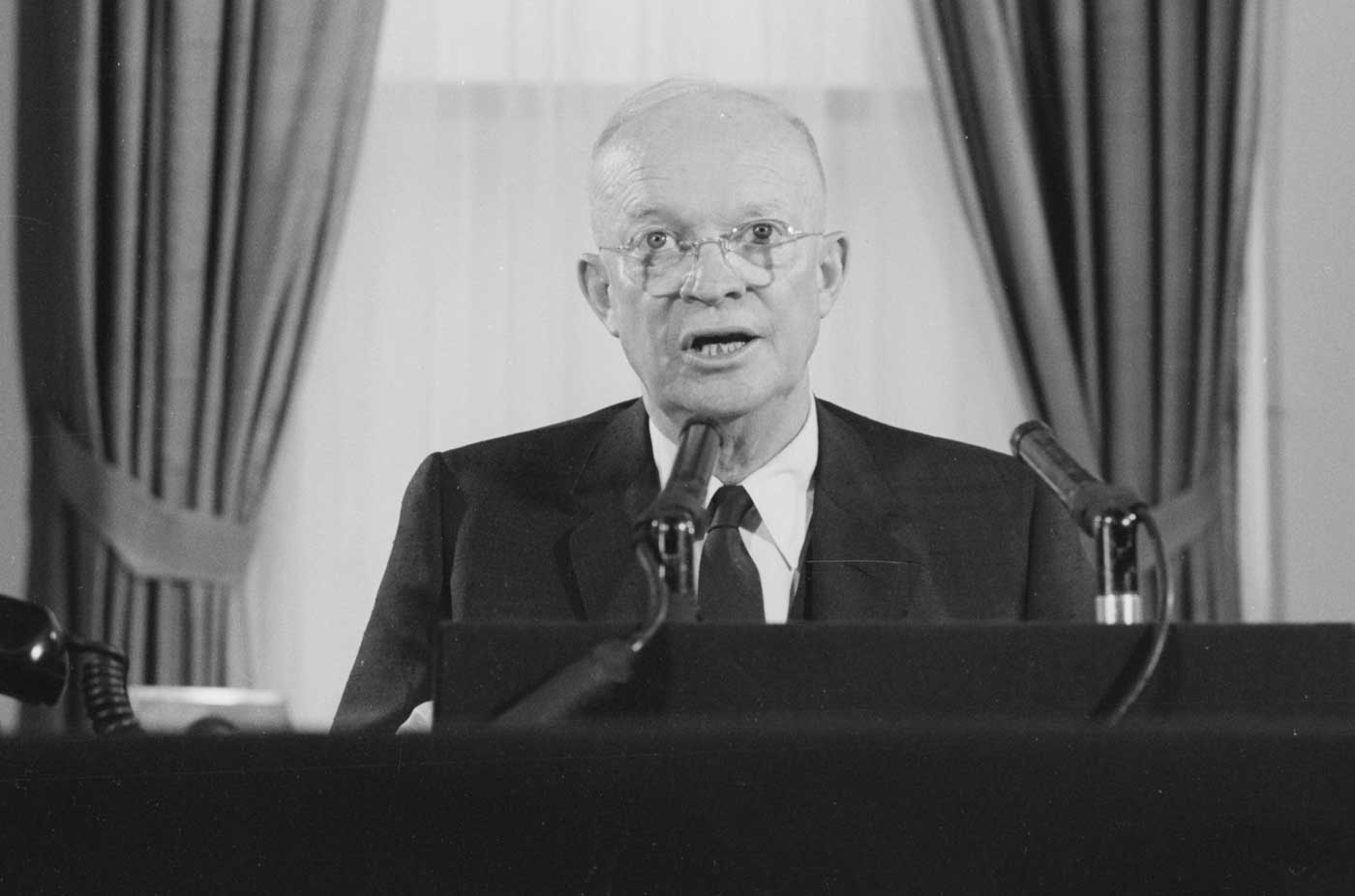

President Eisenhower made it clear in speeches to Congress and to the public that the main purpose of American intervention was to protect the integrity of the Lebanese government and not to support any internal political faction. He called on the United Nations to safeguard Lebanese independence so that the American troops could be withdrawn.

It looked for the most part like time for the Marines to clear the area and leave that intimidation/deterrent mission up to the U.S. Army or the UN. Secretary of State Allen Dulles announced that the U. S. forces would be withdrawn as soon as the Lebanese Government requested their removal. The ball was now in Lebanese hands.

Waiting for a decision, Marine General Wade put most of his force on orders for short-fuse redeployment to the ships offshore and conducted a series of training exercises with Lebanese Army Forces. That culminated in a practice Marine amphibious landing near the biblical town of Byblos, 20 miles north of Beirut. It was the last of the Marine landings in Lebanon until 25 years later in 1982.

Backloading of Marine forces to ships at sea began in mid-September and continued through most of October 1958. On 23 October, the Lebanese formed a new government under General Chehab as president and including representatives from each of the major political parties. The last US Army troops departed Lebanon shortly thereafter.

In the larger scheme of things, it’s hard to tell what it all meant. In hindsight it’s fairly clear that there was little if any connection between the Iraqi Revolution and the factional unrest in Lebanon. That did not mean the experience was meaningless for the troops on the ground. It was a significant lesson in a new way of limited warfare and peacekeeping operations. Lieutenant Colonel Harry Hadd who commanded BLT 2/2 throughout the operation in Lebanon had an insightful observation.

“The conduct of the individual Marine in holding his fire when he can see who is shooting in his direction must be mentioned. When a youngster lands all prepared and eager to fight and finds himself restricted from firing at a known rebel who he sees periodically fire in his direction and in every instance restrains himself from returning the fire, it is felt this is outstanding and indicates good small unit discipline. The situation had to be thoroughly explained to the individual Marine and they understood why the restriction on fire was necessary. Many innocent people could have been killed.”

That lesson was certainly incorporated into Marine Corps doctrine and preached to those of us who went ashore again in Lebanon in 1982-83. We did it the way our nation asked us to do it then as members of the Multinational Peacekeeping Force in Beirut. But times and factional proclivity for violence had changed. We failed to change with it and the second time around in Lebanon cost America 240 Marines and sailors killed in the Beirut barracks bombing incident of October 1983.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

61

61