Japan’s Underwater Aircraft Carriers

October 13th, 2025

10 minute read

On September 9, 1942, residents of Brookings, Oregon noticed a fire to the east of town, near Wheeler Ridge on Mount Emily. About noon, two spotters on the fire lookout tower noted the smoke despite the foggy conditions. The fire spotters and several townsfolk also noted a strange aircraft in the area that day, and when the U.S. Forest Service workers went to the fire site, they found that it had been started by a Japanese incendiary bomb. Fortunately, the area was quite damp, and the fire quickly burned out. The bewildered forest service men turned over parts of the bomb casing, complete with Japanese markings, to U.S. Army personnel.

There were many questions, but only one thing was certain: America had been bombed. But how?

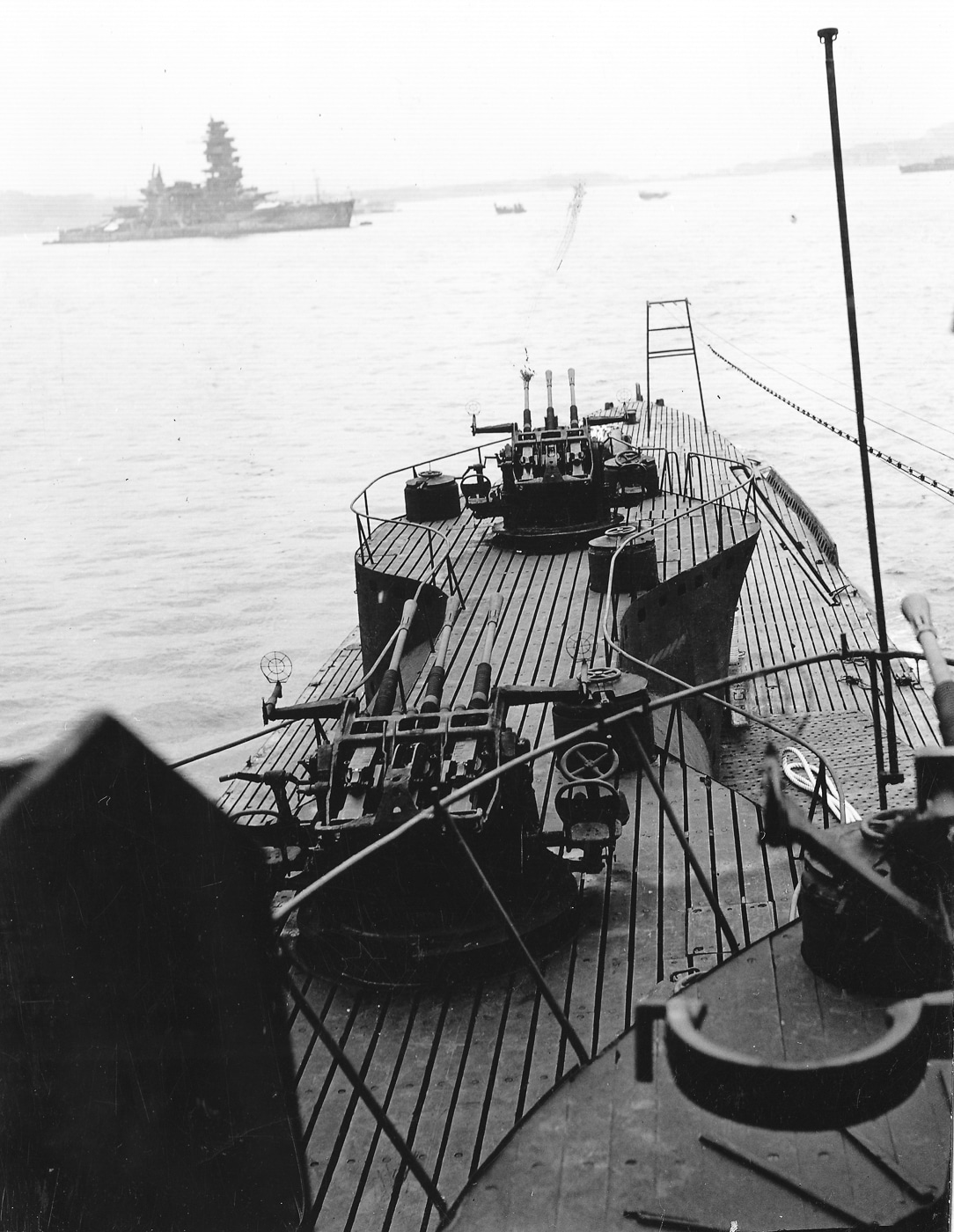

On that September day, Chief Warrant Officer Nobuo Fujita, an Imperial Japanese Navy pilot, and his observer, Petty Officer Shoji Okuda, took off in their Yokosuka E14Y recon aircraft, on their mission to fire-bomb the massive forest near Brookings, hoping to start a significant forest fire with two 168-pound incendiary bombs. They had reached the coast of Oregon in the giant submarine “I-25”, the tiny E14Y floatplane carried in a watertight capsule on the deck of the sub. The I-25 was 356 feet long, weighed 2,584 tons, and had a range of 16,000 miles.

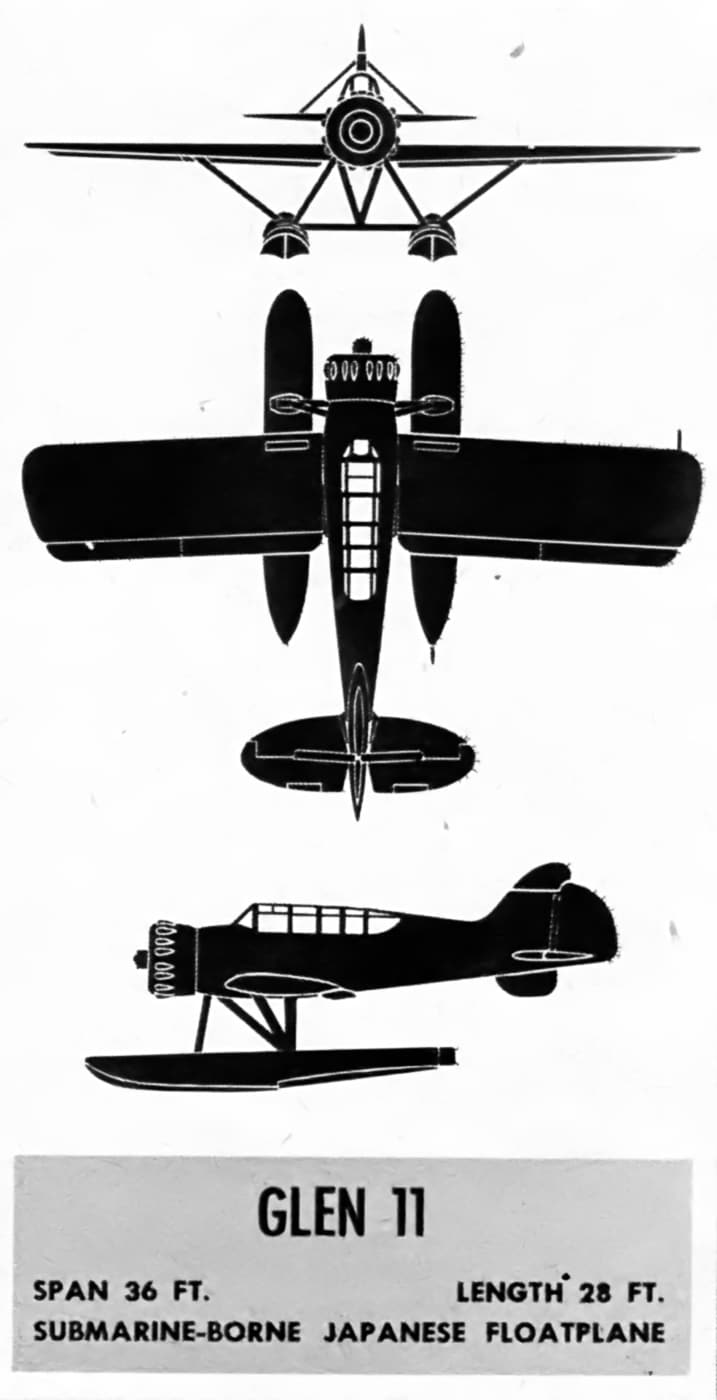

Existence of the Yokosuka E14Y (Type O Small Reconnaissance Seaplane, later codenamed “Glen” by the Allies) was unknown to the U.S. military at that time, and the entire concept of a stealthy submarine “aircraft carrier” was essentially something out of a Buck Rodgers comic. What Japan’s air attack on U.S. soil lacked in effectiveness was made up for in imagination. Fujita’s flight in the E14Y floatplane was somewhat bewildering to the American military, but it certainly provided proof-of-concept for the Japanese, and plans for more powerful attacks were set in motion.

While the September 1942 attack was the only time enemy aircraft bombed the continental United States, it was the second time the Japanese I-25 attacked America. During the night of June 21, 1942, the I-25 surfaced near the mouth of the Columbia River and fired 17 rounds from its 5.5-inch deck gun at Fort Stevens. None of the shots hit the fort and there were no casualties. The artillerymen in the fort could not locate the submarine and their commander opted not to return fire to prevent revealing his position — leading to a major reevaluation of U.S. coastal artillery. Again, although their attack was ineffective, the Japanese proved they could strike America’s west coast.

The Panama Canal Mission

After the Battle of Midway in early June 1942, the Japanese were increasingly on the defensive. Even so, the Japanese continued development of their aircraft-carrying submarines, along with specialized, high-performance floatplanes to use with them.

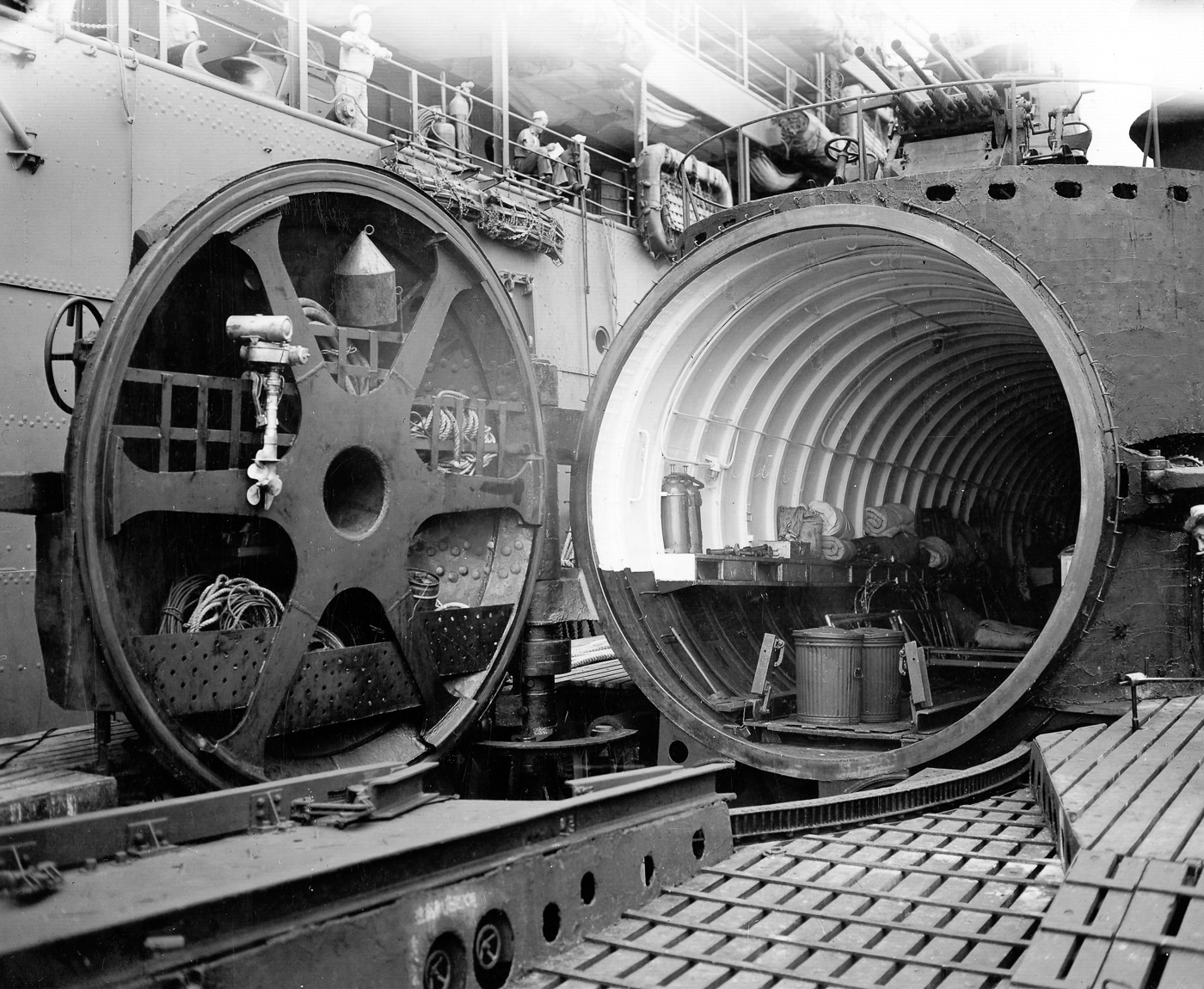

By late 1944, two “Toku-gata” class subs, the I-400 and I-401, had been built. The I-class boats weighed 5,300 tons and were 400 feet long. Each I-400 sub could carry three of the new Aichi M6A1 “Seiran” floatplanes, carried in a watertight hangar at the front of the conning tower. The I-class subs had a range of thousands of miles — and more than enough to reach the USA if they sailed east or west. In late 1942, a fleet of 18 I-class submarines was planned. This number was cut several times, and by the end of the war only three had been completed, with just two available for service.

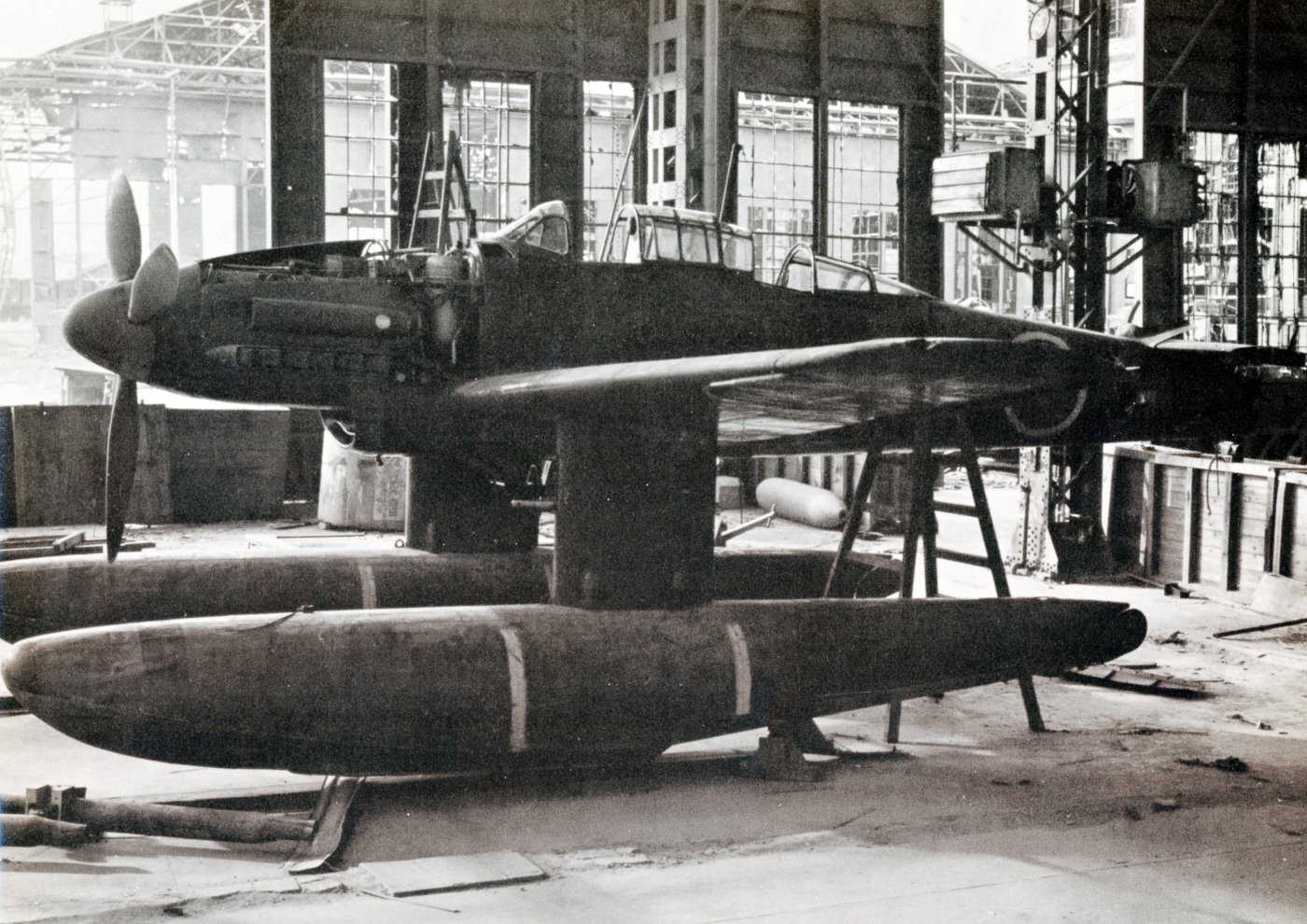

The first Aichi Seiran flight was in November 1943. Using an Atsuto liquid-cooled engine (an inverted V-12, generating 1,400 HP on takeoff), the Seiran’s maximum speed was 295 mph, with a range of more than 730 miles. The engine was rare for a Japanese aircraft, and the Atsuto was a license-built copy of the German Daimler Benz DB 601A. Including two prototypes, there were only 28 of the Aichi floatplanes built. If the war had continued, the Japanese planned to build more than 120 Seiran. The last Seiran was built in July 1945. Others were in various stages of assembly when the end came. The Seiran was a complete secret to the Allies, consequently no code name was given to the aircraft, and it was only discovered in September 1945.

By the autumn of 1944, the Japanese had broadly adopted kamikaze tactics, and it was decided to apply these special attack methods to the floatplane squadron attached to 1st Submarine Division. By January of 1945, the fortunes of war had turned Japan’s big attack plans to lesser ones, and as work on the I-class subs and their Seiran aircraft had ended, a strategic target had been selected.

As the war in Europe was coming to a close, the Western Allies began to shift more assets to the Pacific. Consequently, the Japanese chose to attack the Gaton locks of the Panama Canal. Two I-class subs (the I-400 and I-401, with three Seiran each) would be supported by two smaller AM-class subs (I-13 and I-14, with two Seiran each). The larger I-class subs would refuel the AM-class boats on the journey to Central America.

Approximately six weeks were spent in intensive training for the mission. The aircraft crews studied detailed models of the Gatun locks and how to attack them. A total of ten Seiran aircraft would fly the mission — six armed with torpedoes and the remainder carrying an 1,800-pound bomb. Two aircraft were assigned to attack each lock position.

An important part of the training was the catapult launches. Initially, the Seiran aircraft were assembled and launched with their floats, and this took about 30 minutes — a significant amount of time with the subs being quite vulnerable on the surface. Testing showed that the operation could be handled in slightly less than 15 minutes if the Seirans were launched without their floats.

Time and tide slipped away, and war situation made the training for the Panama Canal mission a moot point. On June 25, 1945, the target was changed, and the 1st Division was ordered to expend its Seiran aircraft in suicide attacks against the U.S. aircraft carriers gathered at Ulithi Atoll.

The Ulithi Operation

Operation Hikari began as a transport mission. The I-13 and I-14 were loaded with four of the new, high-performance Nakajima C6N Saiun (“Myrt”) high-speed recon planes and sent to Truk Island. As the submarine-borne Seiran attack aircraft had but one chance to strike as suicide aircraft, the latest intel on the U.S. Navy at Ulithi was essential. The Myrt recon planes were quickly assembled at Truk and readied to scout the U.S. fleet for the Seiran’s suicide attack.

After the reconnaissance had confirmed the presence of the U.S. aircraft carriers at Ulithi, the I-400 and I-401 would approach from Singapore. Much to the surprise of the Seiran pilots, their aircraft were repainted in U.S. Navy colors for the mission. In their desperation, the Japanese planners intentionally broke the international codes of war, estimating that if the Seirans were seen on their approach to the target, the fake U.S. markings might give them a few moments of disguise to reach their targets. They would be launched without floats, and with their 1,800-pound bomb permanently attached to the belly of their aircraft.

The I-subs were planned to rendezvous within range of Ulithi on the night of August 14th. The attack was planned to occur at daybreak of August 17th. Fate intervened, and on August 16th, the commander of I-401 received the transmission that Japan had surrendered. The unthinkable had happened, and the I-class subs were ordered to return to Japan. On the journey home, all the Seiran were catapulted into the sea with their wings folded (I-401) or were pushed overboard (I-400) to destroy the evidence of their false markings.

U.S. Naval personnel carried out detailed inspections on a large group of captured submarines in Japanese home waters. When Soviet officials were scheduled to make similar inspections, the U.S. Navy scuttled most of them, including the mostly complete I-402. The I-400 and I-401 sailed to Pearl Harbor for more detailed inspection. In early June 1946, the Soviets were demanding to inspect the Japanese super-subs and the U.S. Navy responded by scuttling them off Oahu.

Post-War Assesments

I was able to find a small group of U.S. intelligence reports about Japanese aircraft-carrying submarines, and reports on the I-Class subs after the end of the war:

Japanese aircraft carrying submarines (via Tactical and Technical Trends 1945)

It is reported that about 30 I-type Japanese submarines are designed to carry small float planes in watertight compartments on their decks. Four submarines of similar type carrying midget submarines instead of planes. The latest information regarding the top speed of the I-type submarine is 20 knots surfaced, and 9 knots submerged.

Either of the two types of aircraft noted in (a) and (b) can be carried:

The wings and fuselage are stored in separate tubular compartments which are watertight and located side-by-side, with their axes parallel to the submarine and in prolongation of the conning tower. No catapult or crane is reported, although a portable crane is possible. Time of launching of the plane is estimated by unofficial sources as one hour after surfacing.

- Type 96 observation seaplane, “Slim”, small reconnaissance biplane floatplane. Maximum speed is 170 mph at 11,000 feet. Endurance is 500 miles without load.

- Type Zero observation seaplane, “Glen”, small biplane floatplane. Maximum speed is 190 mph. Endurance is 475 miles.

Sub-based Airplanes via Intelligence Bulletin January 19, 1945

About half of the large cruiser-type submarines carry airplanes. They are used for searching out the enemy and for reconnoitering important places. Because these airplanes are of the small type, and their range is limited. Twenty to thirty minutes are required to assemble them.

Recently a Japanese submarine was pursued by a U.S. destroyer in the Aleutian area. The submarine was forced to dive while the airplane was still assembled, causing great damage to the airplane. It is easy to catapult an airplane, but time is required to swing it up with a derrick after it has landed on the water. A calm sea is necessary.

The Japanese Submarine No. I-401 reports that she met an American X 196 submarine at latitude 40 10 North and longitude 143 32 East at 0400 hours 29 August and was ordered by the Captain of the American Submarine to move directly into the Tokyo Bay. Taking into consideration the circumstances that the position of the Japanese submarine is at the moment near Ominato and also that it is not unlikely the entry of the submarine might cause unfortunate incidents in the Tokyo Bay, where the American Forces are to land on 30 August, we consider it advisable that she be ordered to move direct to Ominato. Urgent reply is desired. Please inform the Commander of the 3rd Fleet of the above if request is accepted.

USS Weaver, 29 August 1945: Commander Hiram Cassidy USN assumed command of Japanese Submarine number 400 (I 15 Class) a t 10301 28 August PA 134 with prize crew from subdiv ENU 6 on board. Position Lat 37-30 North, Long 142-30 East. Fuel on board 450 tons. Flying American Ensign above Jap colors in addition to large black pennant. Maximum speed 15 knots. 1 main motor inoperative. 20 Jap officers and 170 men on board. Seem cooperative. Intend leaving crew on board until reaching Sagami Wan unless otherwise- directed. No ammunition small arms or torpedoes aboard. Short on drinking water, request permission to tie up alongside USS Proteus (AS 19) upon arrival, ETA Point X 03301 29 August.

Biological Attack on USA: Operation PX

As the B-29 Superfortress raids began to devastate Japanese cities in early 1945, many Japanese leaders sought revenge. Several options were considered, but the only reliable “delivery system” was the combination of the I-Class subs and their Seiran bombers. Plans for “Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night” were finalized on March 26, 1945.

In this case, the Japanese Navy worked with Lieutenant-General Shirō Ishii of Unit 731, Japan’s biological warfare unit. The operation was given the codename of “PX” — standing for Pestis bacillus-infested fleas. The Seiran bombers would not carry high explosives on their mission to San Diego, California. Instead, they would carry fleas infested with bubonic plague.

Five of the I-Class and PM-Class subs were scheduled to carry their bio-warfare bombers to San Diego on September 22, 1945. Two atomic bomb raids ended the war before Operation PX could take place. The casualties at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were heavy. The deaths from a biological attack like “PX” were incalculable, and the Allied response would likely have been significant.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

509

509