Smoke ’Em If You Got ’Em: Peters Paper Shells Are Back

May 12th, 2022

9 minute read

The postman handed it to me as if it were a broom. I tore a fingernail on the brown wrap over the long cardboard box. Inside, a spanking-new pump-action shotgun gleamed from folds of oiled paper. The warm walnut came to cheek eagerly, bead bright at the end of the sleek barrel. Shick-a-tick! Oh boy!

At $94, that 16-gauge had obliterated my savings; I had to beg for a box of shells to feed it. In the mid-60s, crimped plastic was replacing card-stock over-shot wads and waxed paper hulls. But the smoke curling from those first empties had an addicting aroma plastic would never match.

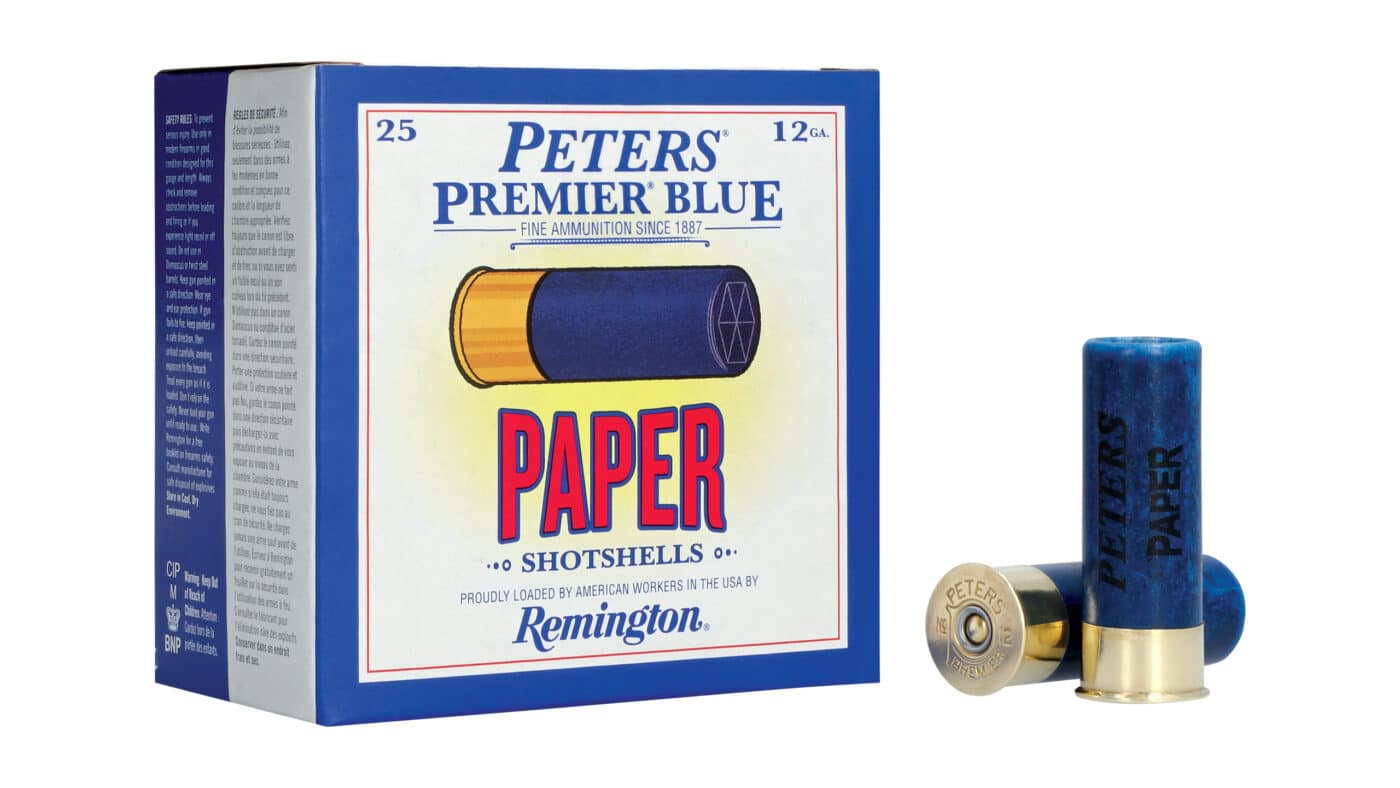

That heady scent came to me again the other day. The shotshells weren’t old, but crisp new Peters loads, with the waxed blue paper of decades past. Artwork on the box matched – images, colors and fonts from gentler times, when the USPS cheerily served customers with post-paid shotguns and 3-cent stamps.

“We designed the box and shells to evoke early days,” explained Jonathan Langenfeld, a Product Engineering Manager at Remington’s Lonoke, Arkansas ammunition plant. Built in the 1970s off I-40 just 10 minutes east of Little Rock, it employs more than 1,000 people and turns out rimfire and centerfire metallic rounds, as well as shotshells. Lead dropped through sieves atop an 11-story tower forms shot for standard Remington loads. Of course, the company also offers lead-free and special shotshells.

“These are special,” Jon assured me. “We looked hard for paper that matched exactly the color of the original Peter’s Premier Blue. The shot is hard, with 5 percent antimony. Heads are brass, not plated steel.” A shotgunner who shatters clays at the nearby Remington Gun Club, he added: “While steel heads are cheaper and common in hunting ammo, brass is easier to size in Ponsness-Warren presses. It’s used in top-shelf target loads. Besides, it’s traditional.”

The only new Peters Blue shotshell available at this writing is a 2¾” 12-gauge, with 1 1/8 ounce of #8 shot clocking a listed 1,145 fps. This load, whatever the brand, ranks among the most popular with trap shooters. It’s also a hit with hunters after ruffed grouse, woodcock, pigeons, doves and quail.

A Passion Project

Langenfeld told me the idea of reviving Peters paper was discussed in 2018, “but the project got real traction after Vista’s purchase of Remington in October 2020. A couple of other manufacturers offer paper shells, but the selection is very limited, and the packaging – well, ours is the best! Not just the material and printing, but the finish. There’s more to an attractive box than most shooters think!”

Producing paper shotshells is a complex process too, and more time-consuming than is the case with plastic hulls.

Skiving the paper is the first step. During WWI among British troops, skiving came to mean “avoiding work.” As slang, that definition persists. But skiving as applied to materials is a shaving process, to taper or reduce thickness. A cobbler makes leather more flexible by skiving it. Colored shotshell paper comes to the factory in huge rolls, each of which will make 25,000 hulls. It is skived to taper and “finish” edges of sheets before they’re rolled and glued into tubes. These dry and cure in a heat-treatment room.

“Initial skiving takes a day per batch,” Jon told me. “Then the paper is rolled and glued and kept for a day under heat to cure. Figure another day for conditioning. Then the 12” tubes are cut into four 2¾” tubes and impregnated with wax to repel water. The tubes are conditioned for another 10 days before they go to the heading machine. Start to finish, a paper shotshell takes 14 days to make. He also added, “it requires more employee time and factory space than a plastic shell.”

There must be a bit of hocus pocus to these operations, as Langenfeld was politely vague when I asked for details and clarification. No matter. Producing your own paper shotshells is about as practical as making your own light-bulbs. For all that, however, paper shells don’t last as long as plastic. “A couple of loadings,” said Jon, “before you’ll find the occasional leak around a battery cup. Wound paper base wads don’t seal as well as do plastic. Paper is easier to crimp – but of course, those creases wear out sooner.” In paper’s favor: “Competitive shooters say recoil is less punishing. Paper is biodegradable. And there’s that smoking-waxed-paper smell … .” Oh, yes.

Driving Demand

The first paper shotshells followed brass ammunition in the mid-19th century, for early breech-loading English fowlers and their American counterparts. (If legend is to be believed, the term “shotgun” originated in Kentucky in 1776.) C.D. Leet Co. of Springfield, Massachusetts, patented a paper shotshell in 1869. Further development kept pace with that of brass shotgun ammunition, but the availability and popularity of paper hulls did not. The first paper shells were sold, empty, in boxes of 100. Shooters were accustomed to handling components separately and had no reason to expect factory loads. After all, the Civil War had just been fought with caplock rifles.

Frank Chamberlin of Cleveland, Ohio, gets credit for the first practical shotshell loading machine, a contraption he showed to Pittsburgh Firearms Co. president J. Palmer O’Neil after a duck hunt in 1883.

As reported in a 1908 issue of Field and Stream, Chamberlin claimed it could load and crimp 400 shells an hour – and promptly demonstrated by chugging through 50 so fast, “his guest was astounded.” After a patent, Chamberlin partnered with O’Neil to form the Chamberlin Cartridge Co. An improved machine with an hourly output of over 1,200 shells followed. They peddled the $1,500 machine to sporting goods outlets, hardware stores and other enterprises that could profit from it. Shooters were soon clamoring for loaded paper shells. (The only holdouts were waterfowlers, who would stay with brass shells until paper got wax waterproofing.) Alas, the components that fed Chamberlin’s loader came from two established ammunition companies. These firms tooled up to serve the booming market and cut ties with Chamberlin. By 1900 he was out of business. Remington bought what remained of Chamberlin Cartridge Co. in 1933.

Despite his relatively short day in the industry’s sun, Frank Chamberlin changed it, and left habits that endured. His loaded shotshells were the first sold in boxes of 25. (Early on, these were called “quarter boxes” and shipped 20 to a wooden crate.) He was first to feature pictures of load-appropriate small game on boxes, a practice Remington revived in the 1920s. And his modestly priced ammunition weaned many shotgunners from loading their own. Between 1887 and 1901, sales of field-ready shotshells increased seven-fold, fueling the fortunes of six major ammunition companies: Peters Cartridge, Remington Arms, Union Metallic Cartridge, United States Cartridge, Western Cartridge and Winchester Repeating Arms.

The Foundation

Brothers Gershom M. and O.E. Peters formed Peters Cartridge Co. in 1887. Gershom was son-in-law to J.W. King, founder of King Powder Co., and upon J.W.’s death in 1881 had become president of King Powder. Peters’ claim that it was first to market “automatic machine-loaded shotshells” is arguable, as the company appeared three years after Frank Chamberlin’s patent. But Peters hiked production rates with steam power and improved the machinery. No longer were workers required to put components in hulls by hand. Delivering 60 finished shells per minute, with less labor than previously required, Peters quickly shouldered its way into the market.

Initially, Peters bought paper hulls from UMC, U.S. Cartridge and Winchester. When it tried to shed that dependence on rival firms by purchasing American Buckle and Cartridge Co. in New Haven, Winchester interfered. But AB&C’s tooling was later sold to Peters. By 1891 Peters was making its own paper hulls, under the “Prize” label. Four years later it built a shot tower, and was soon producing wads and primers as well. With propellant from King Powder, it was a self-contained company. Advertising its ammunition with colorful images on the boxes set it apart from the competition.

In the mid-1890s, King Powder was producing black, smokeless and semi-smokeless powders in its factory, just across the Little Miami River from Peters’ at Kings Mills, Ohio. These propellants fueled a range of Peters cartridges, ironically a result of the competition’s move to throttle access to components. Had shotshell components remained readily available to Peters, it may well not have ventured into “the manufacture of everything pertaining to the ammunition business.”

By the early 1900s, Peters had a range of shotshells. Semi-smokeless powder in its Referee loads offered “velocity equaling the best nitro powders, with low breech pressure.” Smokeless Ideal, Victor and High Gun loads became popular in waterfowl blinds, on uplands and at clay target events. Victor shells of red paper were produced from 1936 to 1956, and hawked to hunters in ads with blue High Velocity loads.

Changing Fortunes

Even before the shooting of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo triggered WWI, Peters supplied metallic cartridges to Great Britain and Russia. Demand for ammunition in Europe prospered the industry stateside until the armistice in 1918. Defunct military contracts and Depression capped that demand. During the 1920s and into the ‘30s, Peters’ investments in its factory failed to turn loss to profit. Early in 1934, the company sold to Dupont-owned Remington Arms, which closed the Kings Mills plant a decade later.

The roller-coaster market in small-arms ammunition hit another high during WWII. Predictably, demand again plunged in its wake. By the late 1950s, when Alcan Cartridge Co. and Robert Cromerford came up with the plastic shotshell, sales and mergers had taken the least resilient companies, leaving only three major ammunition brands. Plastic shotshell hulls gained traction during the 1960s, and the standard rolled crimp with card top-wad all but vanished. Folded-crimp shells were faster to produce – though the fold claimed more of the hull body than did a roll at the mouth, thus decreasing case capacity. For ease of manufacture, almost all shotshells now, paper and plastic, have folded crimps.

But some 19th-century practices endure. “High brass” and “low brass” hulls, for example. In early days, metal case heads were made to cover the hull to the top of the powder column, to prevent occasional burn holes in paper hulls. Bigger powder charges required taller case heads than did target or light upland loads. Double-base (nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine) smokeless powder made high brass unnecessary, as propellant volume was much reduced. Powder columns of even stiff waterfowl loads were short enough to match low or mid-height brass. High and low shell heads endure mainly because generations of hunters have used them as a way to quickly identify loads.

“Tradition matters,” smiled Jon Langenfeld. “That’s why we went to the trouble of re-introducing

Peters Premium Blue shells – and printing a synopsis of Peters’ history on each box. These shells are as good as you can put through your shotgun, but they’re also a nod to what some hunters recall as their best days on the range and in the field.”

Conclusion

He rang off, then. It was quitting time in Lonoke, Arkansas. But most of the afternoon remained here in the Pacific Northwest. Cracking a box of the new Peters Premier shells, I snatched an appropriate shotgun from the rack – a 1950s-vintage pump-shotgun – and slid a blue paper shell into the tube. Snick-snick. The carrier licked it up, and the bolt locked. “Pull!” a disk rocketed from the hand-trap. Bang! It shattered. Instead of jacking the empty free, I eased the slide open and let it tumble into my hand. I brought it up and drew deep of the lazy curl of smoke from its mouth. Years fell away.

“Ready?” Alice had her arm cocked, another bird in the clamp.

“Not yet,” I said. And inhaled again.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

58

58