Did This Spawn the M14?

December 24th, 2019

7 minute read

To get to the M14 rifle, America had to get to the M1 Garand. But where did it start before the Garand? The process took one step, one development, and one cartridge at a time. The quest to put a self-loading rifle in the hands of U.S. troops began in earnest during February 1921, in an environment of greatly reduced military spending, and the short-lived peace in the aftermath of the “War to End All Wars.”

To answer this question, I spent some time going through U.S. Ordnance documents that detail this process. In order to chart the path of American self-loading rifle development, it is important to get a good idea of the condition of American small arms at the end of 1918.

In the Interim

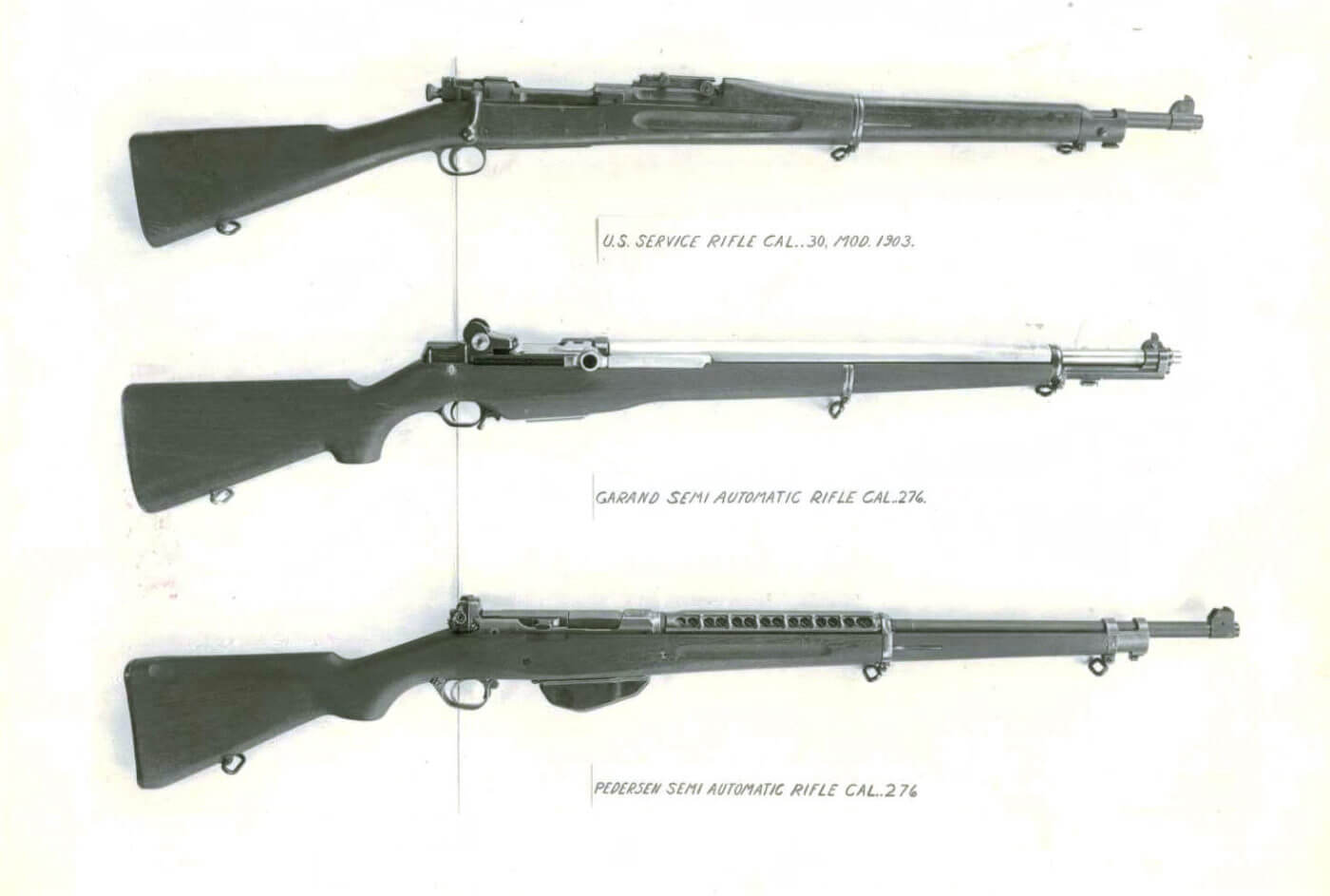

During World War I, in an era of bolt-action rifles, innovative American firearms developers had experimented with several self-loading rifle designs. The U.S. military opted not to put any of these into production. Meanwhile, America’s arms industry was in full swing by 1918. Small arms like the M1903 Springfield rifle (America’s standard service rifle), the M1917 Enfield rifle (America’s most numerous battle rifle in World War I), the Browning Automatic Rifle and the Browning M1917 machine gun had proven themselves on the battlefield.

At the end of World War I, American forces fielded the most advanced and effective small arms in the world. Even as the U.S. government hurried to slash military budgets in the immediate post-war period, U.S. infantry weapons were the envy of international military forces.

Closing the Range

An important aspect of World War I infantry combat that escaped many observers was that combat ranges were closing. The expectations of marksmanship for the individual rifleman had decreased measurably from 1914 to 1918. Rapid, suppressive firepower was increasingly valued, and the rifle was now more often supporting the machine gun, instead of the other way around.

All of this made a lighter cartridge more viable on the battlefield than had been previously expected — and was considered for a time. In the short term however, cartridges smaller than .30 caliber would continue to be greeted with skepticism. Other than pistols and submachine guns (and the unique M1 Carbine), the U.S. would remain committed to the .30-06 cartridge well into the 1950s.

The Pedersen Solution

As the Army Ordnance Bureau pursued three self-loading rifle concepts in the early 1920s (the Bang Rifle, the Thompson Auto-rifle, and the Garand Model 1919 rifle), the problems of those designs (using the standard .30 caliber cartridge) manifested themselves in high chamber pressure and excessive heat, and in creating rifles that were ultimately very heavy.

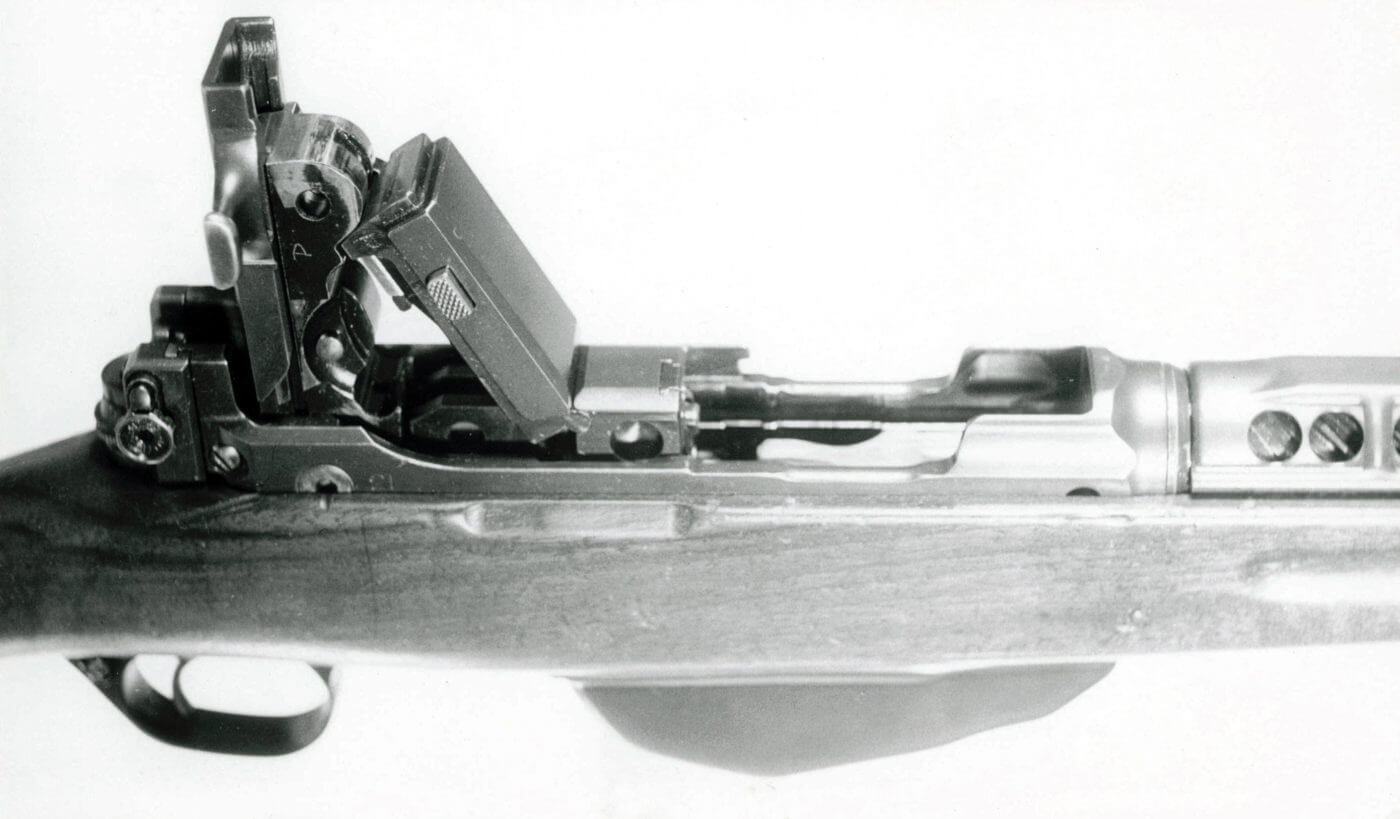

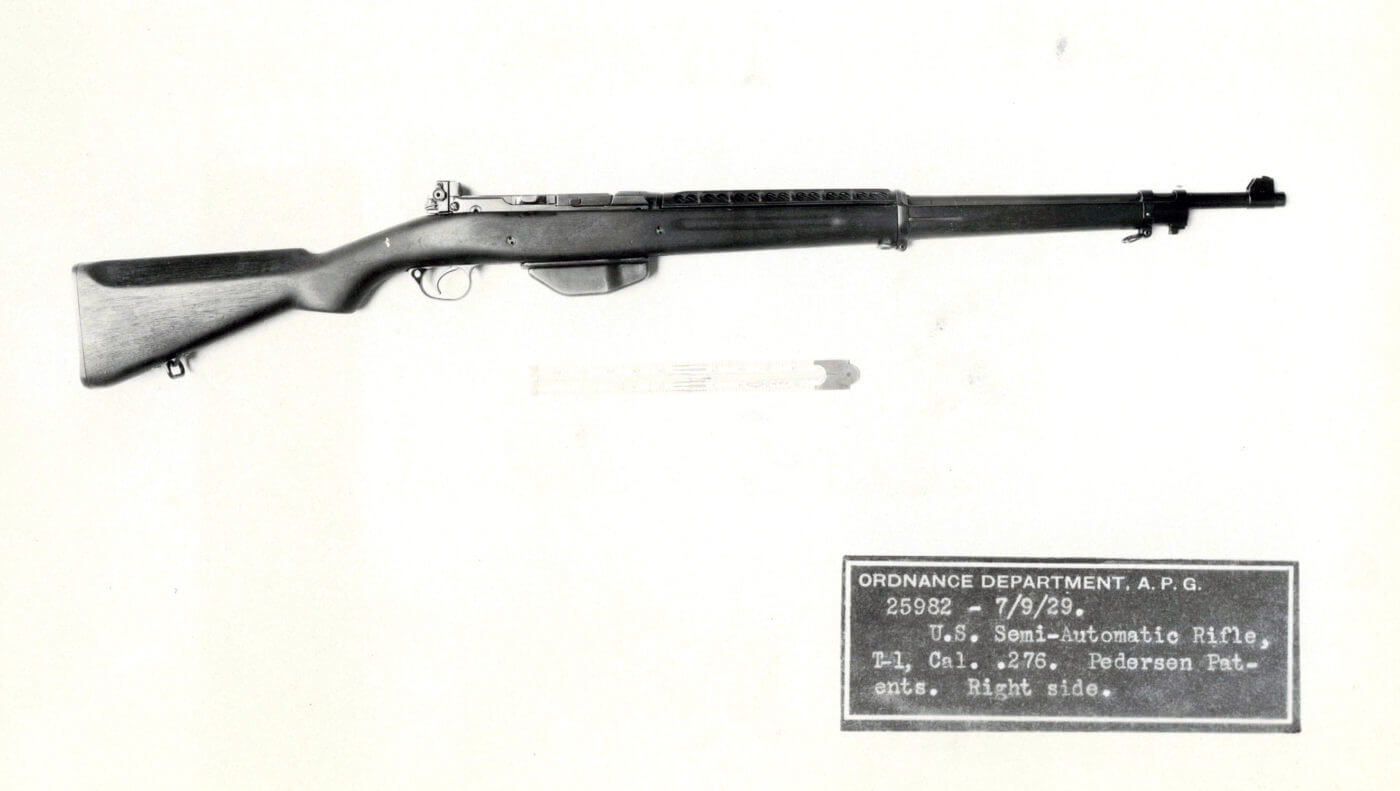

In the middle of this development, noted firearms designer John Pedersen offered a unique proposal to the Ordnance Bureau that approached the challenge from a unique perspective. Pedersen’s semi-auto rifle concept featured a unique toggle-joint locking system. He proposed a significant change in the cartridge, stepping back from the .30-06 and using a slightly less powerful, but still effective cartridge in the 6.5mm to 7mm range.

The Bureau of Ordnance was impressed with Pedersen’s proposal, and in 1923 they awarded him a contract that provided a developmental budget, office space and a salary. Pedersen was also granted the right to patent his work and collect royalties if his rifle was adopted by the U.S. military. Initial tests were described as promising:

“The pilot model 7mm Pedersen type rifle was demonstrated to the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4, Major General Fox Connor, and others interested, at Camp Sims, D. C. (the rifle range for the D.C. National Guard) on December 11, 1925. Approximately 200 rounds were fired in this demonstration and the rifle functioned very well. Some firing was done at a target at range 200 yards, and the accuracy was good, considering that the gun is a first model and that the ammunition development is not complete.”

What Were the Goals?

America’s self-loading rifles were not developed in a vacuum. The Ordnance Bureau provided rifle designers with a detailed list of their wants and expectations. The following is a condensed list of those expectations, developed in February 1921.

The rifle must be a self-loading type, adapted to function with cartridges not less than .25 caliber or greater than .30 caliber, of good military characteristics, and preferably to fire the U.S. cartridge, caliber .30, model 1906. It must be simple and rugged in construction and easy of manufacture. It should require but little more attention than the regular service rifle when placed in the hands of the average soldier.

The following features are considered necessary:

(a) The rifle must be simple, strong and compact. Weights should be well balanced and so placed that the essential strength is given to components requiring it. Ease of manufacture should be a guiding factor in preparing the design.

(b) The mechanism must be well protected from the entrance of sand, rain, or dirt, and should not be liable to derangements due to accidents, long wear and tear, exposure to dampness, sand, etc.

(c) Components of the mechanism should be the fewest possible, consistent with ease of manufacture and the proper functioning of the weapon. Parts requiring constant cleaning, or which may require replacement should be designed with a view to ease of dismounting by the use of not more than one small tool, preferably the service cartridge.

(d) The rifle must be so designed that the magazine while in position in the rifle may be fed from clips. The magazine may be detachable, but this is not considered desirable. The breech mechanism must be so designed as to preclude the possibility of injury to the firer due to premature unlocking. It is preferable that the bolt or block be positively locked to the barrel at the moment of firing. The capacity of the magazine should not exceed ten rounds.

(e) The firing mechanism should be so designed that the firing pin is controlled by the trigger and sear direct; that is, the bolt mechanism should move forward to the locking or firing position with the firing pin under the control of the trigger and sear mechanism, so that the cartridge is not ignited until the trigger is pulled to release the firing pin. The bolt or block should remain open when the last cartridge in the magazine has been fired. In case a detachable magazine is used the insertion of a new magazine should not release the bolt.

(f) The trigger pull, measured at the middle point of the bow of the trigger, should be not less than 3 or more than 5 pounds. The trigger action should be similar to that of the present service rifle, i.e., it should have a light first pull, after which there should be no appreciable backward motion until the sear is released.

(g) An efficient safety or locking device must be provided, permitting the rifle to be carried cocked and with a cartridge in the chamber without danger. The rifle should remain cocked and ready for firing when the safety device is unlocked.

(h) The weight of the rifle with magazine empty and without bayonet, should be a minimum consistent with proper functioning, and in no case should exceed 10 pounds.

(i) The rifle must be so designed as to give good balance and be adapted to shoulder firing. The general appearance and outline of the gun should be, as nearly practicable the same as the United States rifle, model 1903.

(j) The accuracy of the rifle should be comparable to that of the present service shoulder rifle.

Expectations vs. Reality

When the M1 Garand was adopted in 1936, there was no fully automatic variant of that rifle. Eventually the M14 was developed and added selective-fire capability during the 1950s. Once in service, the Army reversed its field and removed the full-auto capability from many of its M14 rifles.

In Subsection (h) the Board demands a rifle of not more than 10 pounds. The .276 Pedersen rifle weighed in at a little over 8 pounds. The M1 Garand would be accepted for service at 9.5 pounds. The M14 would be accepted at 9.2 pounds, but its weight climbs to 10.7 pounds with a fully loaded 20-round magazine.

Soldiering On

While the M14 may have had a short service life, it led to the creation of the civilian-legal semi-automatic M1A rifle from today’s Springfield Armory. The result is an outstanding rifle that has excelled on the competition fields and gives civilian shooters a chance to own a rifle inspired by this classic military rifle. It’s available with either a classic walnut stock or a rugged black composite stock.

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

132

132