Does Bullet Weight Matter for Self-Defense?

October 1st, 2025

11 minute read

Bullet weight for self defense is one of those topics that gets thrown around a lot in gun shops and online forums. And honestly? It matters. But probably not in the way most people think.

Here’s the reality. When considering carrying a 9mm with 115-grain hollow points or 147-grain rounds, the difference on paper looks significant. Lighter bullets go faster. Heavier bullets move more mass. But when you’re talking about a self-defense scenario inside seven yards, which is where most defensive shootings happen, the practical difference gets muddier. Shot placement beats bullet weight every single time.

That said, bullet weight does influence penetration depth, expansion reliability, recoil management and how your ammunition performs through barriers. If you carry concealed, you need to understand these trade-offs. Not because you’re going to calculate foot-pounds of energy in the moment, but because choosing the right defensive round means you’ve done the homework beforehand.

Understanding Bullet Weight Basics

Bullet weight gets measured in grains. One grain equals 1/7000th of a pound, or about 0.0648 grams. So when you see 124-grain 9mm ammunition, that’s roughly 8 grams of projectile leaving the barrel. The grain weight only refers to the bullet itself and not the entire cartridge with the brass casing and powder.

For 9mm, the most popular concealed carry caliber in the United States, you’ll typically see three common bullet weights: 115 grain, 124 grain, and 147 grain. There are others, but these are the most common. These aren’t arbitrary. They represent different ballistic philosophies. Lighter 115-grain rounds achieve higher velocities, usually around 1,150 to 1,200 feet per second from a full-size handgun. Mid-weight 124-grain loads sit in the middle ground, often favored by NATO and many European law enforcement agencies.

Heavy 147-grain bullets move slower but can carry more momentum into the target. Many of these loads are subsonic, meaning they don’t break the sound barrier. If you are shooting a suppressed gun, that may be an important consideration.

The same principle applies across calibers. In .40 S&W, you’ll see 155-grain, 165-grain and 180-grain loads. I know the .40 has fallen out of favor with many, but the cartridge remains effective. I recommend reading Dan Abraham’s article about the .40 S&W for additional insight.

In .45 ACP, 230-grain ball ammunition is the standard, with jacketed hollow points typically ranging from 185 to 230 grains. The pattern holds: lighter bullets tend to go faster, heavier bullets tend to penetrate deeper and retain more energy at the target.

Notice I said “tend to” as these are not hard rules. Bullet design and many other factors come into play. Bullet weight does not exist in a vacuum. You’ll notice throughout the article that I am hesitant to use absolutes when it comes to bullet performance. There are a lot of variables, and little in this article is as simple as a 2+2=4 math problem.

How Bullet Weight Affects Terminal Performance

Terminal ballistics is what happens when a bullet hits soft tissue. This is also where grain weight starts showing its hand. To stop a violent attacker with a firearm, generally, one of two things must happen: you shut off the central nervous system (CNS) with a shot to the brain and/or spinal cord (hard) or cause significant, rapid blood loss (also hard, but slightly easier than a precise shot to the CNS). Rapid blood loss will lead to hypovolemic shock, which will eliminate the attacker’s ability to fight.

To achieve hypovolemic shock, the bullet(s) have to penetrate deep enough and cause enough tissue damage to cause a lot of bleeding. Shots to vital areas like the lungs are more likely to cause rapid blood loss than to non-vital areas. Bullets that expand can cause more bleeding. So can multiple bullets. But to reach vital areas, the bullets have to penetrate through skin, muscle, fat and bone.

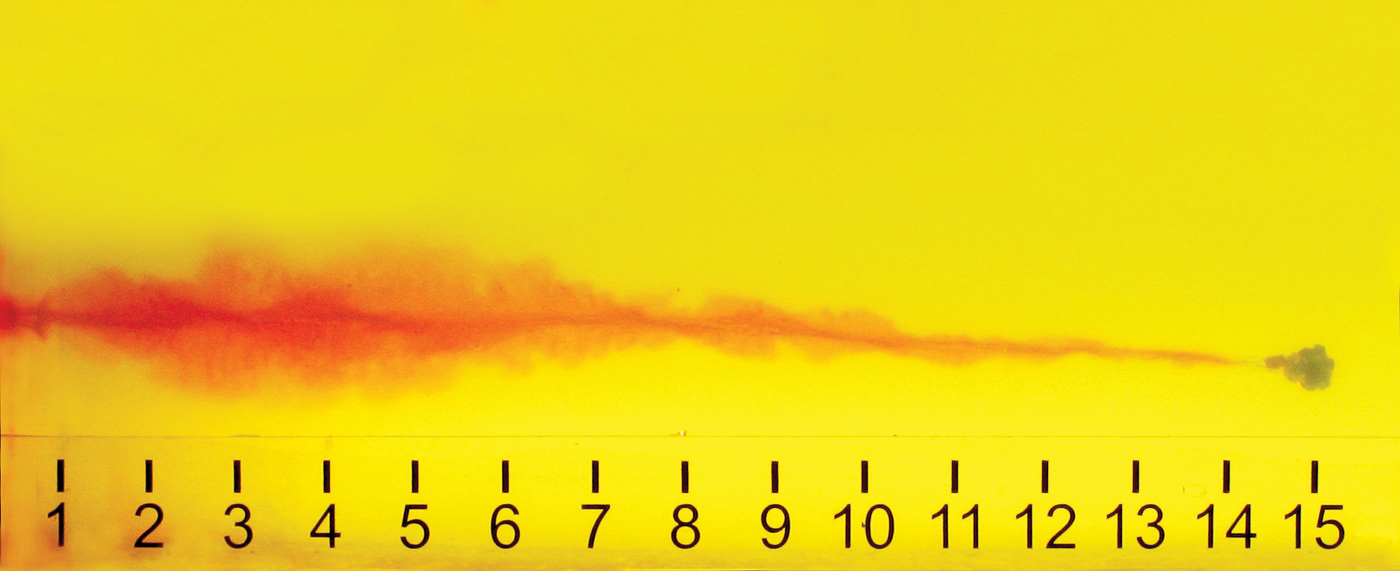

The FBI established a testing protocol after the 1986 Miami shootout that changed how law enforcement selects ammunition. Their standard requires handgun bullets to penetrate between 12 and 18 inches in calibrated 10% ballistic gelatin. Less than 12 inches risks failing to reach vital organs. More than 18 inches risks overpenetration and hitting unintended targets.

Heavier bullets generally penetrate deeper because they carry more momentum. Physics dictates that momentum equals mass times velocity. A 147-grain 9mm bullet moving at 950 fps has more momentum than a 115-grain bullet at 1,200 fps. This can translate to better performance through barriers like heavy clothing, wallboard, and even auto glass, which are all scenarios the FBI protocol tests. For example, Speer Gold Dot 147-grain loads routinely achieve 14 to 16 inches of penetration through heavy winter clothing. That’s ideal performance according to the FBI standard.

But penetration isn’t the whole story. Expansion also matters. A jacketed hollow point bullet that expands creates a larger wound channel, which causes more tissue damage and faster incapacitation. Here’s where lighter bullets sometimes have an advantage. Higher velocity promotes reliable bullet expansion. A traditional 115-grain jacketed hollow point (JHP) bullet moving at 1,150 fps tends to expand more reliably than a slower 147-grain load at 950 fps. Additionally, the size of expansion can be more with a faster moving bullet.

There’s a tension here. More expansion means less penetration. Less expansion means deeper penetration but a smaller wound cavity. Modern premium defensive ammunition from companies like Federal, Speer, Hornady, and Winchester has gotten very good at balancing these competing demands. The engineering involves jacket thickness, hollow point cavity design, and even polymer plugs that prevent clothing from clogging the cavity. While velocity remains an important factor in reliable expansion, high speed is less critical than it was with traditional hollow point projectiles of the past.

Weight retention is another factor the FBI scores. If a bullet fragments and loses mass during penetration, it bleeds momentum and energy. Penetration tends to be more shallow. While some companies make a good case for intentionally fragmenting rounds, many people believe a single expanding projectile is the more reliable choice.

Many modern self-defense bullets are bonded, chemically or mechanically, to the lead core to prevent separation and maintain weight better than conventional jacketed hollow points. Hard barriers like a windshield often caused jacket separation with old bullet designs.

Recoil and Follow-Up Shot Speed

Recoil isn’t just about comfort. It directly impacts your ability to put accurate follow-up shots on target. And in a defensive shooting, multiple hits matter more than a single perfect shot. In my study and experience, multiple shots are the norm, not the exception.

Lighter bullets typically produce less felt recoil in the same firearm. The power factor calculation of bullet weight times velocity divided by 1,000 gives you a rough metric. A 115-grain 9mm at 1,150 fps has a power factor of 132. A 147-grain load at 990 fps comes in at 145. Higher power factor can mean more felt recoil energy. But felt recoil is subjective and depends on gun weight, grip design, and shooter technique.

Some shooters find 147-grain 9mm has a different recoil character. It’s slower and feels more like a push than a snap. The 115-grain rounds feel sharper and faster. Neither is objectively better. What matters is which you control more effectively. If you shoot 115-grain ammo better and can make faster accurate follow-ups, that’s your answer. If the heavier recoil impulse of 147-grain ammunition doesn’t slow you down, that round might be your best pick.

Compact carry guns complicate this equation. No matter how well designed, a Springfield Hellcat or snub revolver don’t generally generate the same velocities as an Echelon or other full-size service pistol. Lighter guns can also amplify felt recoil. A 147-grain load that’s manageable in a 1911 DS Prodigy can feel significantly snappier in a compact. And when velocity drops below a certain threshold, hollow point expansion can become unreliable. This is why some manufacturers offer short barrel loads specifically engineered to expand at lower velocities.

Real-World Defensive Shooting Considerations

Let’s talk about what actually happens in defensive gun use. Many self-defense shootings with handguns occur inside seven yards. At that distance, the ballistic differences between 115-grain and 147-grain bullets are minimal. Both will hit essentially the same point of aim. Both have enough energy to do the job if you hit vital anatomy.

Stopping power is a loaded term that gets misused constantly. There’s no magic bullet that guarantees one-shot stops. Incapacitation depends more on shot placement than grain weight. Hits to the central nervous system and causing rapid blood pressure loss are the reliable way to stop an attacker. Everything else is a matter of pain compliance or psychological surrender.

Matching Ammunition to Your Carry Gun

Your specific handgun plays a huge role in which bullet weight performs best. Barrel length directly affects velocity. A 9mm load that generates 1,150 fps from a 4.5-inch service pistol barrel might only hit 1,050 fps from a 3-inch subcompact. That velocity loss may impact expansion reliability.

When loads are developed at the factory, matching velocity to the bullet is done to achieve reliable expansion. Even with modern designs, hollow points need a minimum velocity threshold to open properly. Drop below that threshold and you essentially have a slower-moving full metal jacket that overpenetrates.

This is where ammunition selection requires actual testing. Buy several different brands and grain weights. Shoot them through your specific carry gun into properly calibrated ballistic gelatin if possible, or at minimum test for reliability and point of impact. Not all guns shoot all ammunition equally well. Some pistols prefer heavier bullets. Others are more accurate with lighter loads. The only way to know is to test.

For me, reliability is non-negotiable. A defensive round that doesn’t feed, fire, extract, and eject 100% of the time in your gun is worthless. Some compact pistols with tight feed ramps don’t like certain hollow point designs. Some older 1911s choke on anything that isn’t 230-grain hardball. Modern 1911 pistols, like those from Springfield Armory, don’t typically have the same issue. Test your defensive ammo. And be realistic: if your gun won’t run modern hollow points reliably, either fix the gun or change ammunition.

Premium Defensive Loads by Bullet Weight

If you’re carrying 9mm, certain loads have proven themselves in both FBI testing and real-world use. For me, Federal HST is the gold standard. Available in 115, 124, 147, and even 150-grain versions, HST consistently delivers excellent expansion and penetration across the full range of FBI barrier tests. I like the 124-grain +P load, and it is what many law enforcement agencies issue.

I also consider the Speer Gold Dot as an excellent choice. I’ve been issued these rounds when in law enforcement and can attest to their effectiveness. I have equal confidence in the HST and Gold Dot. The bonded construction means it holds together through barriers better than most. For compact pistols, Speer makes Gold Dot Short Barrel loads specifically designed to expand at reduced velocities.

Hornady Critical Defense and Critical Duty fill two different niches. Critical Defense uses a polymer Flex Tip insert to prevent hollow point clogging and is optimized for standard pressure loads in compact guns. Critical Duty is loaded a bit hotter, designed for police work. Both can be effective, and I wouldn’t lose any sleep if I was carrying them.

Winchester Ranger-T and PDX1 Defender perform exceptionally well. The T-Series bonded hollow point has sharp talons that promote reliable expansion. They are available in 115, 124, 147, and 127-grain +P+ configurations. Law enforcement agencies that don’t use HST or Gold Dot often carry Ranger-T. The 147-grain Ranger-T penetrates deeply and expands consistently across all barriers.

For .45 ACP, the classic 230-grain load is hard to beat. Federal HST 230-grain and Speer Gold Dot 230-grain both perform excellently. The slower velocity doesn’t hurt expansion as much in .45 because you’re starting with a larger diameter. Some carriers prefer 185 or 200-grain +P loads for higher velocity, but standard pressure 230-grain ammunition works fine. I’ve always been a fan of the 200-grain “flying ashtray” load, but have settled on the Gold Dot load for its improved consistency.

Don’t miss Mike Boyle’s article about the effectiveness of the .45 ACP.

Training Ammunition vs. Defensive Loads

You need to train with ammunition that approximates the recoil and point of impact of your defensive loads. But hollow points are expensive. Premium hollow points run $1.00 to $2.00 per round. Shooting 200 rounds in a training session is expensive and not sustainable for most people. The solution is finding practice ammunition that mimics your defensive load’s ballistics without the premium price.

The typical decision many people make is to carry defensive ammunition and train with inexpensive full metal jacket rounds. The recoil impulse and point of impact will be close enough when you match up bullet weights. Target loads are readily available and cost about $0.25 to $0.40 per round. Commercial rounds should feed reliably and produce similar felt recoil to defensive loads.

Even if you train primarily with cheaper ammunition, periodically run your defensive loads through your carry gun. Once a month, shoot a magazine or two of your actual carry ammo. This confirms it still functions reliably, verifies point of impact, and keeps you familiar with the defensive round’s recoil. It’s also smart to replace your carry ammunition annually. Bullets in a carry gun can get chambered and unchambered repeatedly, which can set the bullet back into the case or damage the hollow point cavity.

Common Misconceptions About Bullet Weight

The internet loves absolute statements. “Always use heavy bullets.” “Light and fast beats heavy and slow.” The truth is more nuanced. Heavy bullets don’t automatically penetrate better. Light bullets don’t automatically expand. Neither will hit a vital zone without the user doing his job.

People also overestimate how much barrier performance matters to citizens carrying for self-defense. The FBI protocol includes auto glass and steel because federal agents might have to shoot through a vehicle. Outside of the law enforcement context, the odds of needing to shoot through a car windshield are vanishingly small. Bare gelatin and heavy clothing tests are far more relevant to civilian defensive use. I don’t think you don’t need to prioritize barrier performance if it comes at the cost of other attributes like manageable recoil.

The idea that you can compensate for poor marksmanship with bigger bullets is perhaps the most dangerous myth. Shot placement is everything. A center mass hit with a 9mm 115-grain hollow point is infinitely more effective than a miss with a .45 ACP 230-grain. Accuracy under stress depends on training, gun fit, trigger control, and recoil management. If you shoot a lighter recoiling load more accurately, that’s likely the correct choice regardless of what the grain weight evangelists claim.

Team Springfield explores the differences between the 9mm and .45 ACP here.

The Bottom Line

Bullet weight affects terminal performance, recoil characteristics and barrier penetration. Heavier bullets tend to penetrate deeper and retain energy better. Lighter bullets tend to produce less recoil and often expand more aggressively. The optimal choice depends on your gun, your ability to control recoil, and your specific defensive needs. For compact guns, consider ammunition specifically designed for short barrels regardless of grain weight.

What matters most is choosing quality defensive ammunition from a reputable manufacturer, testing it thoroughly in your carry gun, and training enough to hit your target under stress. Everything else is optimization at the margins. Shot placement beats bullet weight. Reliability beats theoretical performance. And the gun you have with you beats the perfect gun at home.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

7

7