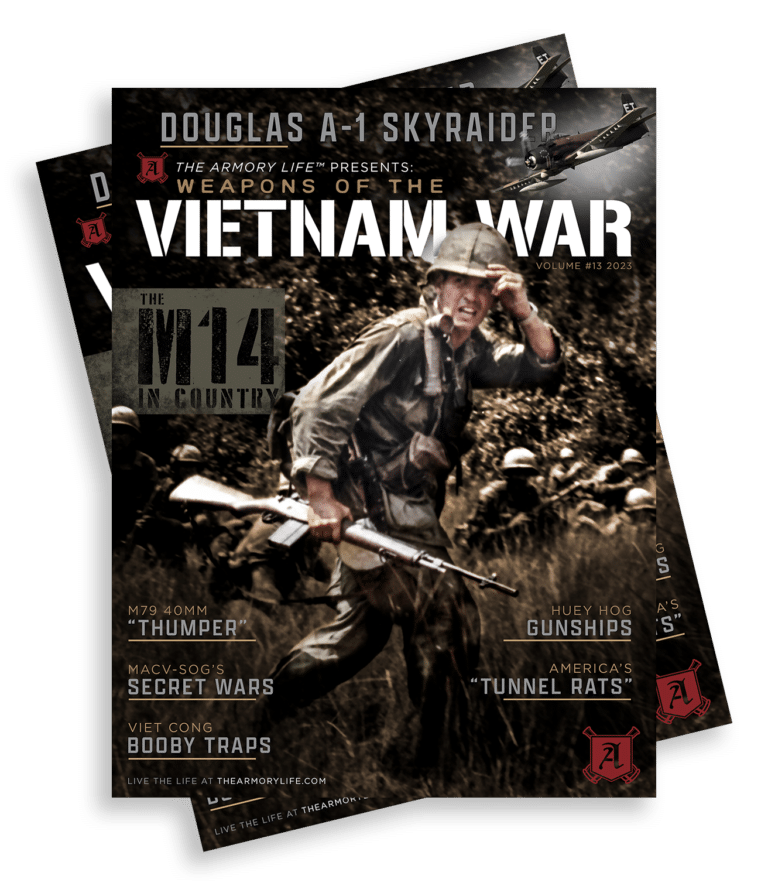

The M14 “In Country”

December 3rd, 2019

7 minute read

Much has been written about the M14, most of it about the rifle’s development and surprisingly little about its use in combat. The select-fire M14’s time in action was relatively short, but those who fired it in anger during the Vietnam War will never forget the last American military rifle constructed of walnut and steel.

The M14 Concept

At the end of World War II, the U.S. Military had an unusually high number of small arms types, using a wide range of ammunition: the M1911 pistol (.45 ACP), the Thompson and M3A1 submachine guns (.45 ACP), the M1 Carbine (.30 Carbine), the M1903 Springfield and M1 Garand rifles (.30-06), the Browning Automatic Rifle (.30-06), and the Browning M1917 (water-cooled) and M1919 (air-cooled) machine guns (.30-06). All of these were fine weapons, but U.S. small arms logistics had become unduly complex.

During 1944, U.S. Ordnance began development of a new cartridge—the 7.62mm T65. This would later be slightly modified (during 1954) to become the standard 7.62×51 NATO round. To fire it, a new M14 rifle would update the proven M1 rifle, leveraging the new NATO round to specifically replace the Garand and the squad-automatic BAR—while it was also believed that the selective-fire M14 eliminated the need for submachine guns.

The M14 concept represented practical thinking: a single rifle filling multiple roles while using the same ammunition. From a logistical standpoint, it all makes sense. However, in actual practice no military has ever been able to make it work across the board. Specialized troops with special weapons exist for a reason. But, on its own, the M14 and its powerful cartridge had much to offer.

Changing Times, Evolving Enemies

Behind the Iron Curtain in the 1950s, the Soviets slowly developed the SKS rifle and AK-47 rifle (both chambered in 7.62x39mm). When the AK-47 finally entered service in 1956, U.S. Ordnance described the new weapon as a “submachine gun”, and the Kalashnikov design was not given much credence—U.S. Ordnance particularly disdained the Soviet intermediate cartridge. Meanwhile, the M14 was adopted as the U.S. Military’s standard rifle in 1957.

By the early 1960s, the U.S. mindset about battle rifles was challenged by a growing number of insurgent actions around the world. The light weight and high firepower of the communist AK-47 made guerrilla forces more competitive on the battlefield than ever before.

In response, U.S. Ordnance quickly placed its focus on the AR-15 rifle, and by 1963 more than a thousand of the 5.56mm rifles had been tested in Vietnam. U.S. Special Forces adopted the AR-15 during 1963, and with favorable reports on the new rifle and its ammunition coming from Southeast Asia, momentum was quickly building for a change in battle rifles. In March 1964, the M16 rifle entered large-scale production, and by 1969 it had become the U.S. Military’s standard service rifle.

The M14 in Vietnam

Modern evaluations of the M14’s combat performance seem to quickly devolve into shouting matches between fans of the M14 and the M16. Suffice it to say that they are both excellent rifles, and no shooter is “wrong” if they have a preference. Also, it is important to remember that given a choice, an infantryman will choose everything. He wants light weight coupled with great firepower. He wants reliability and accuracy. He wants tremendous shoot-through-coverand man-stopping knock-down power. Coupled with that he wants all the magazine capacity he can get.

And while no one begrudges the infantryman his many wants in a battle rifle, there has never been a firearm that gives him everything he desires in just one gun. Ultimately, the American fighting man uses what he is issued, and he has an irrefutable history of using his service arms well.

Could the U.S. Military have performed just as well on the battlefields of Vietnam if the M16 had not replaced the M14 as the primary rifle? I believe the battlefield results would have been similar, as the combat qualities of the American rifleman have always been paramount. Advanced training in marksmanship and fire control could overcome the M14’s less-than manageable qualities when used as a full-auto weapon, and it was also more than capable in semi-auto mode.

Modifications to the M14 were certainly necessary, beginning with a fiberglass stock to replace the original walnut and birch types that tended to swell in the jungle environment. Meanwhile, every infantryman tends to find his rifle to be too heavy at some point. At 10.5 lbs. loaded, the M14 was about 2 lbs. heavier than the AK-47 or the M16, and comments from the troops often reflect this. U.S. troops in WWII complained that the M1 rifle was too heavy as well—but the large amount of deceased Axis troops suggest that the Garand rifle’s performance was just fine.

As a counterpoint to the weight issue, the M14’s 7.62x51mm cartridge was powerful enough to muscle through jungle foliage. Marines describe that, in the absence of an M60 machine gun, the M14 offered the next strongest alternative. In Vietnam, the tactical conditions could vary greatly between one firefight and the next, and the M14 rifle could deliver a high level of firepower, with good accuracy at longer range, whenever called upon. And it certainly earned a legion of fans in the jungles of Vietnam.

From the Source

I recently spoke to an old friend who had considerable experience “in country,” and with a wide variety of U.S. infantry weapons. Captain Dale Dye enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in January 1964. He served in Vietnam in 1965 and 1967 through 1970, surviving 31 major combat operations. He emerged from Southeast Asia with numerous decorations, including a Bronze Star for valor and three Purple Heart medals for wounds suffered in combat.

He spent 13 years as an enlisted Marine, rising to the rank of master sergeant. He was chosen to attend officer candidate school and was appointed a warrant officer in 1976. He later converted his commission and was a captain when he was sent to Beirut with the multinational peacekeeping force in 1982-83.

When I asked him about the M14, Captain Dye commented: “The M14 was a rifleman’s rifle and most Marines carried it with enthusiasm early in the Vietnam War. I can distinctly remember guys trying to hide their favorite M14 when the word came down that we were going to be issued the M16.

Despite the best efforts by some commands, many Marines continued to carry an M14 for quite some time after the switch-over was ordered. There was just a certain factor of trust in that rifle. Or maybe it was some kind of Marine Corps ‘mojo’ but it seemed reassuring to carry a weapon that looked, felt and shot like a ‘real’ rifle.”

It’s All Relative

Taste, and trust in rifles is clearly a generational issue. My father was an infantry sergeant in World War II. When he looked at an M16, he thought they were not “proper” rifles. My grandfather, a World War I infantryman, would likely have looked at the M1 Garand with suspicion, considering it inelegant and brutish compared to his M1903 Springfield rifle. My brothers and I considered rifles like the M16 to be completely normal, and truly appreciate the semi-auto AR-15 variants designed for the civilian market.

Combat seems to have an “evening-out effect” about the opinions of small arms. In that light, many of the combat lessons learned in Vietnam about the capabilities of the M14 were overlooked. Since the turn of the millennium, our military has been “rediscovering” the rugged M14’s powerful capability, much to the dismay of America’s enemies.

Alongside the select-fire M4 Carbines and M16 rifles serving on the battlefield, the U.S. Military M14 also serves. Elements of the U.S. Special Operations Command use the Mk14 Enhanced Battle Rifle (the EBR) as a designated marksman rifle, and in Afghanistan the U.S. Army assigns two M14 EBR-RI rifles per infantry platoon.

Civilian-Legal Sibling

While the M14 is still serving as a U.S. Military rifle, civilian shooters can thank Springfield Armory of Geneseo, Illinois, for offering a semi-automatic, civilian-legal version of this rifle in its M1A. Proven on the competition fields and exhibiting the timeless beauty of wood and steel (although you can get it with a black composite stock if you so desire), the M1A is a wonderful opportunity to own the civilian sibling of a proven American service rifle.

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

1257

1257