Is Your Carbine’s Zero Wrong?

January 14th, 2024

7 minute read

Pull a new AR out of the case, peer through some sights, and one of the first questions will invariably be “What distance should I zero this stuff at?” I could easily regale you with ballistic charts and simply say that “at x distance you’ll be y inches high and that’s why it’s better than z”, but that would be a little disingenuous.

Frankly, I don’t think one zeroing scheme is better than another. However, for practicality’s sake you’ll want a zero that is essentially point-and-shoot within your desired effective range. Whether that’s 100 yards and in or from zero to 300 yards, there are a few viable options from which you can choose.

[Be sure to read our article on how to dope a scope.]

To help keep things on track and provide context, I’m using a SAINT Victor 5.56 rifle with a 16” barrel shooting some flavor of 55- to 62-gr. FMJ bullet at about 3,000 fps in my examples. Currently, this is probably the most common AR configuration going, shooting the most common ammunition available.

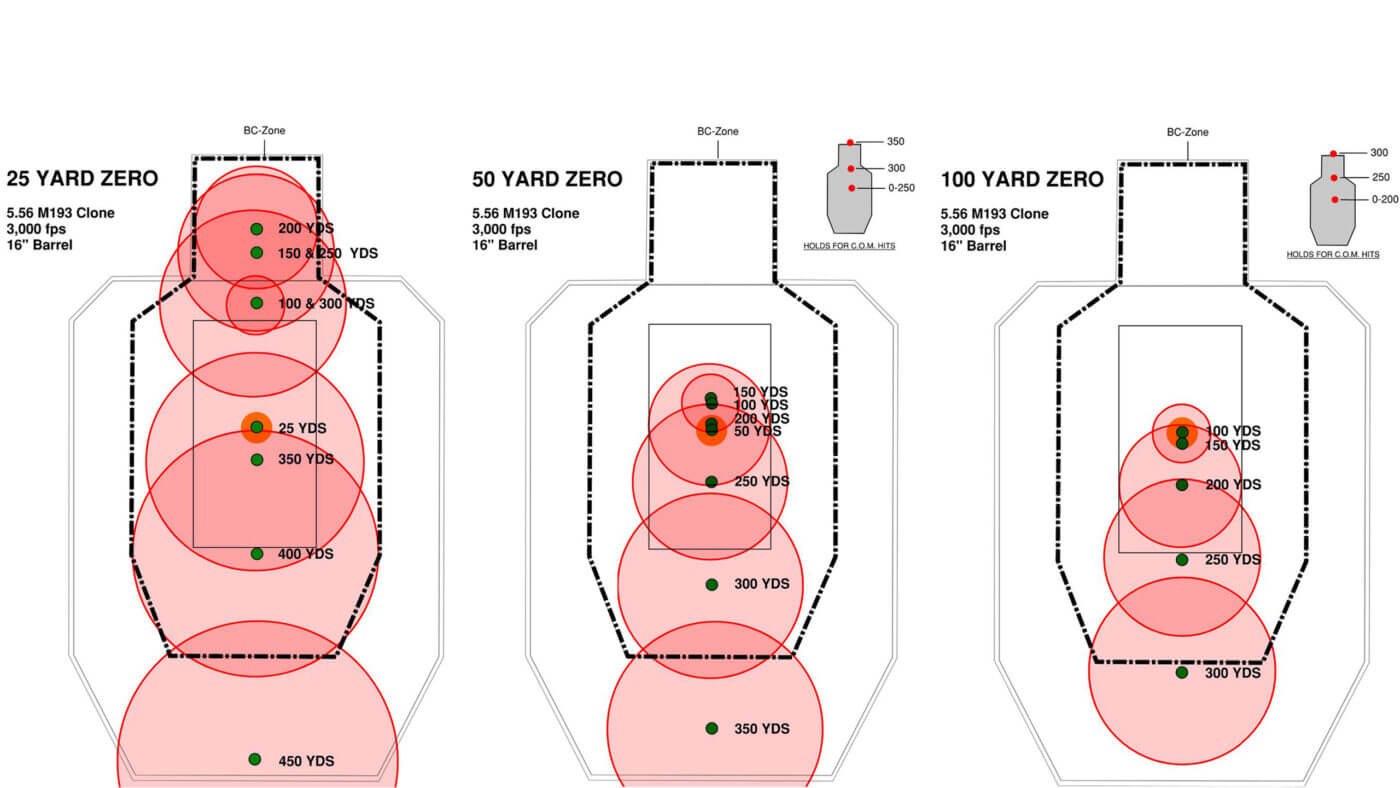

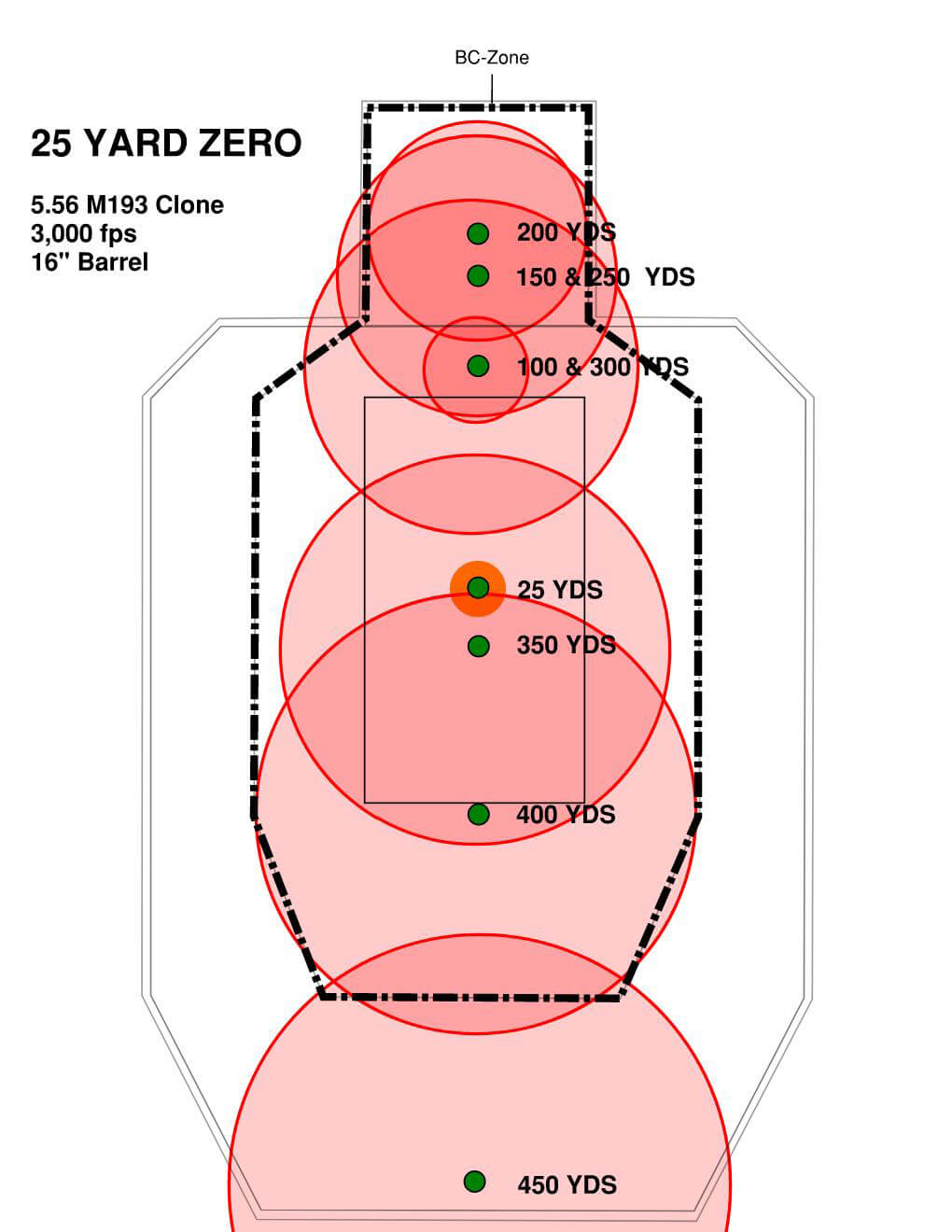

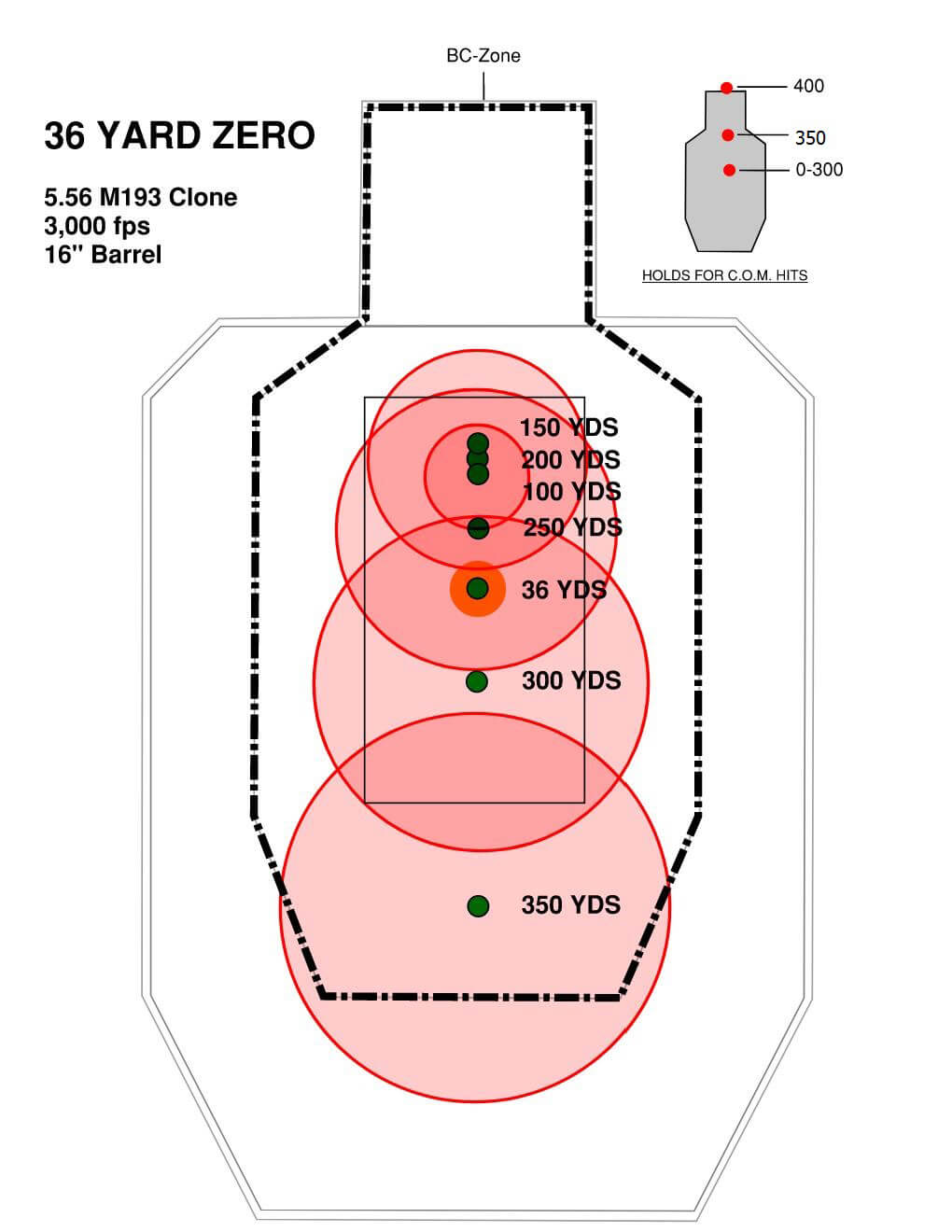

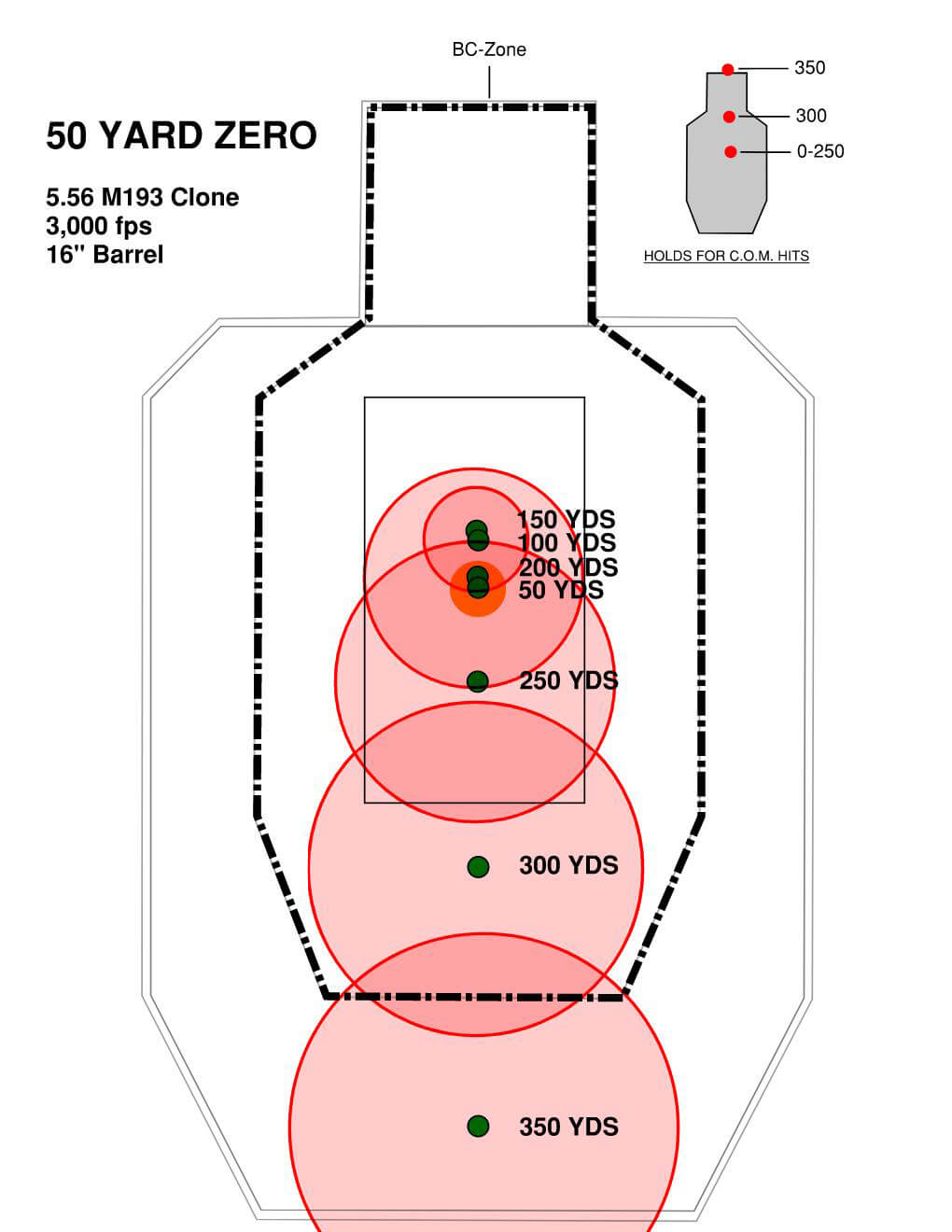

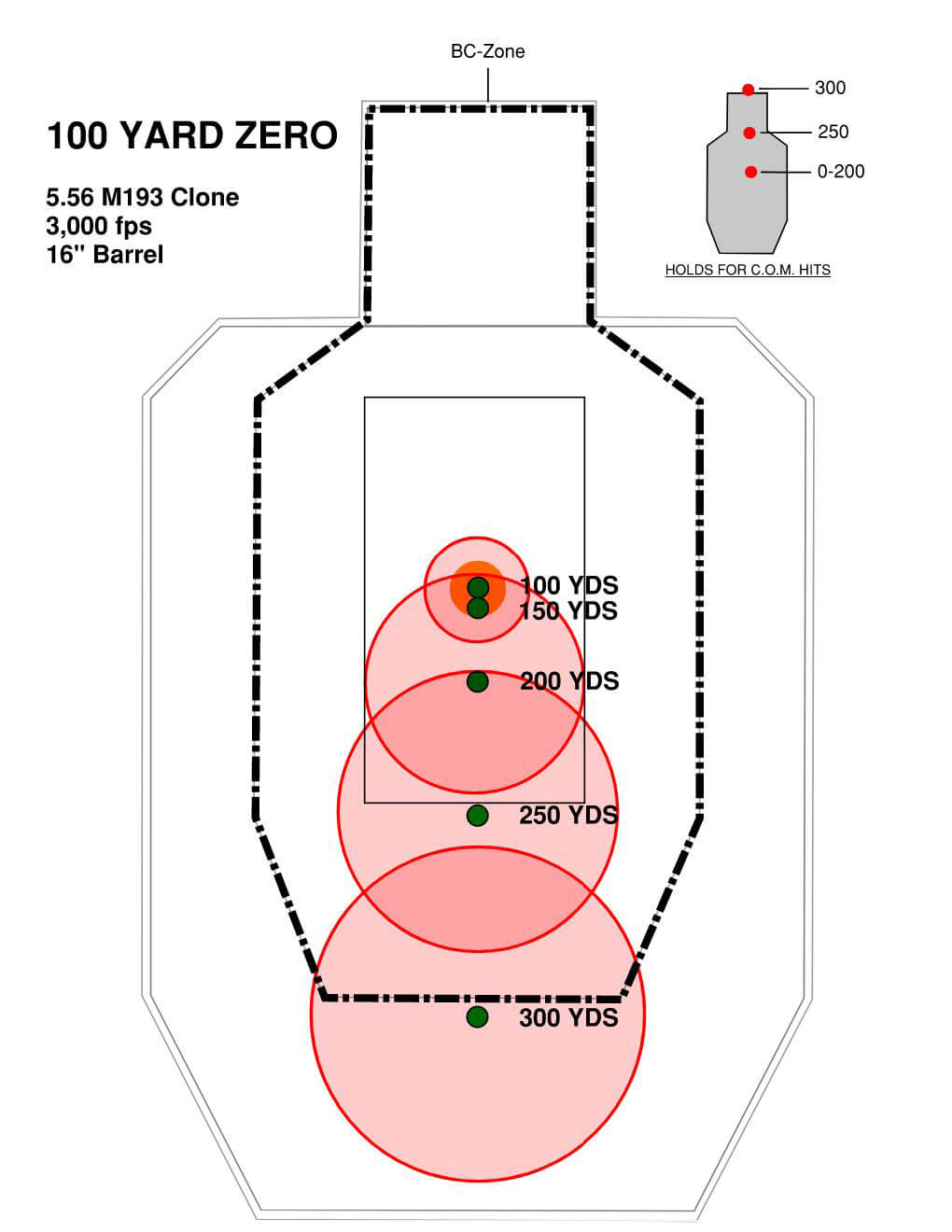

However, let’s be honest … in the hands of the average shooter, this combination is probably good for 3 MOA on a good day. Sometimes it may do better, sometimes worse. The overlaid circles in the included illustrations help to visualize what that 3 MOA extreme spread translates to on a target at a given distance to get beyond arbitrary ballistic figures.

[Learn how to use a BDC reticle here.]

25 Yard Zero

Even though I don’t recommend the 25 yard zero, I’m starting here because it is suggested so often, but is also often misrepresented as a 25/300 yard zero. Two minutes and a ballistic calculator will show you this zero creates an arching trajectory that rises about 9” above the line of sight at 200 yards.

The problem is that it forces you to have to think when to hold under a certain amount on closer targets and when to hold dead on. In the military, we were told to hold low up to 250 meters and then hold dead on for 300 meters. That’s all well and good when your target is 20″x40″, but it starts to get trickier on smaller targets. I can also tell you from experience that when you’re amped up and the lizard brain takes over, you’ll really only be thinking point and shoot.

[For an additional view on the subject, check out How to Zero in an AR-15.]

36 and 50 Yard Zero

That brings me to these two options, which I’d like to talk about together because they’re pretty similar and do well to exploit the advantages of a practical carbine. Now, the arguments that I’ve read on each of these techniques could put a good, old fashioned Ford vs. Chevy debate to shame.

Like a lot of those situations, though, the points argued are based on personal bias and the actual differences are pretty minimal. To see for myself how these two zeros stack up, I took two similarly set up rifles to the range, one zeroed to 50 yards and the other zeroed to 36 yards.

For better or worse, the 36 yard zero is basically a hybrid that flattens out the St. Louis Arch of a trajectory the 25 yard zero creates while still providing a decent maximum range. Compared to a 50 yard zero, its peak trajectory is slightly taller, about 4” above line of sight between 150-200 yards.

With the rifle zeroed at 36 yards, I can reasonably expect to hit a BC-Zone target out to 300 yards without excessive hold-overs. If I need to push out a bit farther, I can just hold level with the shoulder line or top of the target for 350 and 400 yards, respectively. To me, the 36 yard zero makes things about as simple as they can get for a multi-purpose rifle that could be used for range, home defense or duty use.

All that being said, the 50 yard zero continues to be one of my favorite zeroing schemes because it’s versatile, proven and effective. The rifle zeroed at 50 yards shot a little flatter with a max ordinate of just a few inches above the line of sight. This affords me the ability to be a little more precise on smaller targets out to 200-250 yards without hold-overs. If I need to shoot farther than that I can aim at the shoulder line to push out to 300 yards or hold on top of the head for 350. Logistically, it may also be easier for some shooters to get a 50 yard zero since many ranges may not have the facilities available to set up and shoot 36 yards.

At the range I ran through some drills to work on accuracy and precision. Failure drills were shot at the 10, 7 and 5 yard lines, while the hostage taker was done at the 10 after running to make a button hook turn. In both exercises I didn’t feel I had to work harder to get hits using one zero or the other. So long as I accounted for my height over bore, they both worked about the same.

For all intents and purposes, I don’t think you’re going to be let down or at a severe disadvantage if you choose either one over the other.

100 Yard Zero

Zeroing a carbine with open sights or a red dot at 100 yards isn’t intuitive, but the concept has been gaining ground in recent years for certain applications. The chief benefit to using a 100 yard zero is that whether your bullet is going 2,500 fps or 3,000 fps it is the peak trajectory. That means from 0-100 yards you only need to be concerned with your height over bore when shooting a target.

To me this makes the 100 yard zero a perfect choice for a carbine that will be used in close terrain where long shots will be limited. The 300 yard shots are still doable, but as target distances increase you’re going to need to know the specific holds for your set up out to that distance, so it’s important to really know your gun.

Depending on your sighting system and target size this could end up obscuring your target, so keep that in mind if you plan to use this zero. If you’re concerned about getting a good zero at 100 yards, you can always start at 50, adjusting so that your impacts are about ¾” low, and then confirming at 100 yards. Chances are you’ll be very close, if not dead on.

Closing Thoughts

I can’t tell you which zero distance is the best one; that’s really going to be up to you, your skill level and the set-up of your rifle. If you’ve read all this and still aren’t sure of the answer, start with a 50 yard zero and go from there.

Whichever distance you do zero at, I recommend shooting out to as far as possible so that you know what you, your rifle and your ammunition are capable of doing. I’ll leave you with this tip: if you have astigmatism like I do and your red dot looks wonky, flip up the small rear aperture — it will help focus the dot for a better defined aiming point.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

665

665