The Evolution of U.S. Military Rifle Cartridges

August 3rd, 2021

7 minute read

Cartridge rifles came late to U.S. armed forces. The Model 1803 Harpers Ferry, the first military rifle produced by an American armory, preceded the Model of 1819, our first to use interchangeable parts. The 1841 Mississippi rifle was the first U.S. percussion infantry arm. Colonel Jefferson Davis requested it for his volunteer Mississippi regiment. His superiors demurred; President Polk didn’t. In 1855 this rifle got a 58-caliber barrel to fire a conical bullet developed by French officer Claude-Etienne Minie in 1846. Under-size for easier loading, this bullet had a hollow base that expanded on firing to “take” the rifling.

In 1856 the Mississippi rifle was replaced by an improved Model 1855. Fueled by black powder from a paper cartridge the soldier tore and emptied into the muzzle, the three-groove, 40-inch barrel sent .58 “Minie balls” at 1,100 fps. The Civil War triggered mass production of Model 1861 Springfields. By 1865 a million of these rifles would be built, many sub-contracted by Springfield Armory. Early on, rifles and muskets with flint ignition were hurriedly converted to percussion fire. Confederate troops typically used British-pattern Model 1853 Enfields.

The Union Army followed the Model 1861 Springfield with the Model 1863. A decade later the breech-loading Model 1873 cartridge rifle appeared. A “trap door” hinged at its front gave access to the chamber. Fired case withdrawn, the soldier inserted a fresh round and snapped the door shut. The 1873’s .45-70 round used 70 grains of black powder to send a 405-grain bullet at 1,125 fps from carbine barrels, 1,285 fps from 30-inch rifle barrels. The 1873 Springfield would equip U.S. troops until the Norwegian-designed, U.S.-modified Krag-Jorgensen in .30-40 (our first smokeless cartridge) was adopted in 1892.

An aside: Between 1866 and 1873 the Army issued trap-door Springfield rifles in .50-70 Musket, or .50 Gov’t., which hurled a 450-grain bullet at 1,260 fps. Springfield Carbines, introduced in 1870, fired the .50 U.S. Carbine, its 400-grain bullet clocking 1,200 fps. Neither saw action in a war. As late as 1934, New York distributor Francis Bannerman & Sons sold .50-70 Springfield rifles and cartridges.

The bolt-action Krag-Jorgensen is named for Ole Krag, Superintendent of Norway’s Kongsberg Armory, and engineer Erik Jorgensen. American variations (1892, 1896, 1898) were late reaching troops. Most U.S. regiments in Cuba during the Spanish-American War in 1898 carried 1873 Springfields! With its repeating mechanism and the smokeless .30-40 Krag starting 220-grain bullets at 2,200 fps, the Krag-Jorgensen trumped the Springfield in every way. Absence of smoke was a great blessing. Black powder smoke drew enemy fire and curtained the battlefield.

Where There’s Smoke…

Alas, smokeless powder didn’t ignite as easily as black. Adding fulminate for a hotter spark led to cracked cases. Cause: mercury residue. Absorbed by black-powder fouling, it attacked the zinc in cases left clean by smokeless fuel. A non-mercuric primer, the H-48, came in 1898 for the Krag. Its detonating component, potassium chlorate, didn’t harm cases; however, the remaining corrosive salts caused rust.

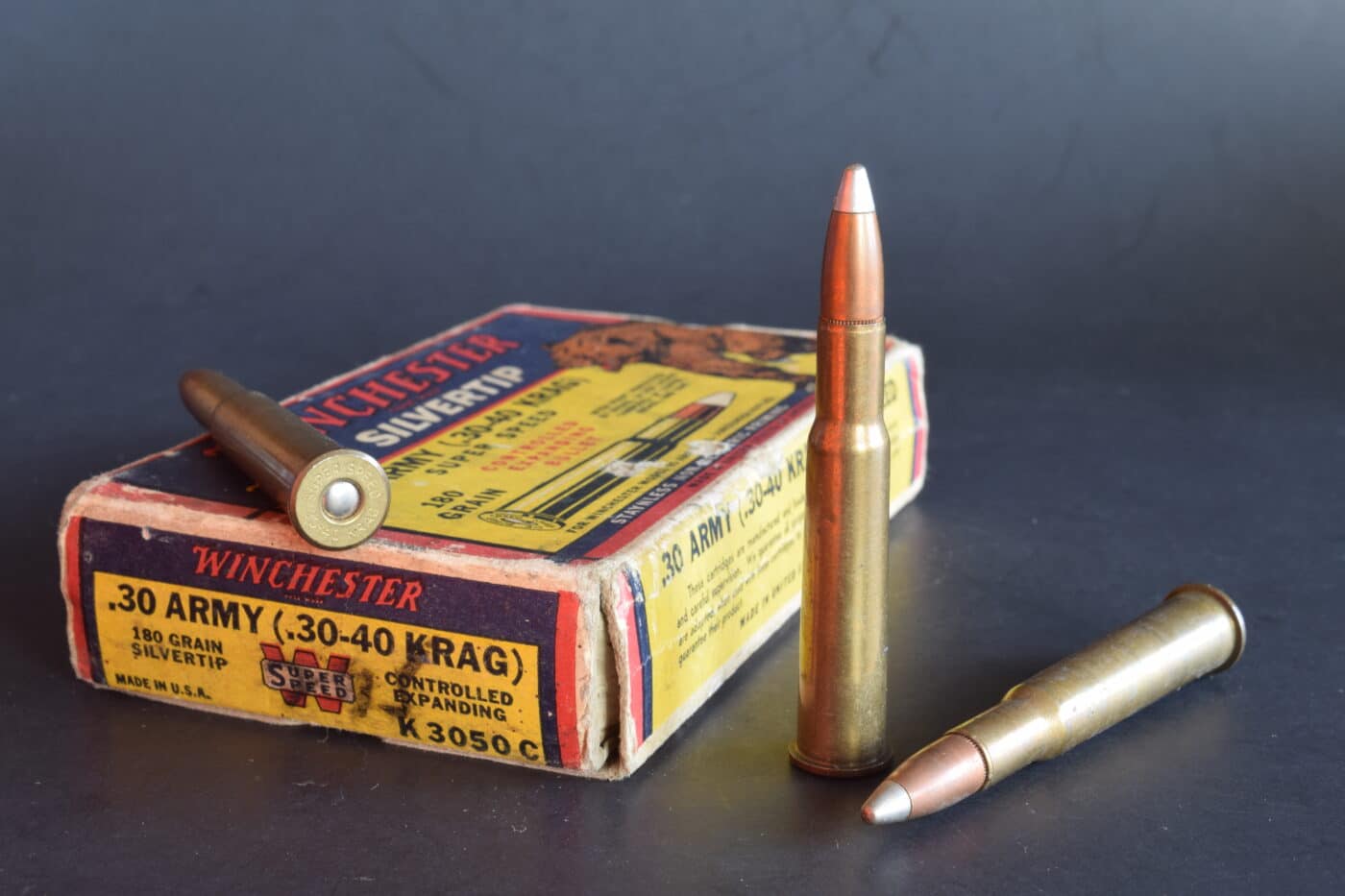

Also known as the “.30 Army” and “.30 Government,” the .30-40 Krag quickly became popular as a hunting round in Remington Rolling Block and Winchester 1885 and 1895 rifles. But plans to replace the Krag rifle began not long after the Army adopted it. Fed by stripper clips, Spanish Mausers in 7×57 had maintained withering fire. U.S. armorers designed this loading feature into a fresh bolt rifle in 1901. Its 30-caliber 220-grain bullet at 2,300 fps matched Germany’s 8×57 with a 236-grain bullet at 2,125. The 1903 Springfield was ready for tests in 1905 when the U.S. paid Mauser $200,000 for design patents it had used.

A year after the .30-03’s debut, Germany adopted a pointed 154-grain 8mm bullet at 2,800 fps. U.S. response: the Ball Cartridge, Caliber .30, Model 1906. It spat a 150-grain bullet at 2,700 fps from a case shortened .07, to 2.494. All .30-03 rifles were recalled for re-chambering.

Like the .30-40 Krag, the .30-06 began life as the “.30 Government.”

The Great War strained rifle production in England and the U.S. To counter the shortage of 1903 Springfields, Winchester and Remington contracted to build rifles on the British Enfield design. Instead of .303 British, the “U.S. Rifle, Model 1917” fired the .30-06. The advantage of a high ballistic coefficient at long-range prompted a new load, with a 173-grain spitzer at 2,646 fps. It kicked hard. In 1939 the Army adopted a 152-grain spitzer at 2,805 fps. With the M1 Garand rifle, it helped the U.S. win WW II.

John C. Garand developed a primer-actuated self-loading rifle by 1920. A gas-driven Garand rifle in .30-06 later beat out the short-recoil-operated Johnson semi-automatic to earn U.S. Army adoption in 1936. Our first self-loading military rifle, the M1 Garand was also first with an “M” designation, which in 1925 replaced “Model” to identify service arms. The number reflected chronology. The Garand used a top-loading clip that, unlike stripper clips for Springfields, went with the cartridge stack into the magazine well. It ejected automatically after the last round was fired.

Toward the Future

By this time, service ammunition had non-corrosive priming, developed first in Germany in 1901. It was especially helpful in self-loading mechanisms. The U.S. Army specified such priming for the .30 Carbine round, issued with its namesake firearm beginning in 1938. Essentially a rimless version of the obsolete .32 Winchester Self-Loading, the .30 Carbine sent 110-grain bullets at 1,990 fps from an 18-inch barrel. Jonathan “Ed” Browning (John’s brother) contributed to M1 Carbine design; but he died in 1939, a year before the Army blessed the project. David Marshall “Carbine” Williams, then serving a sentence at a North Carolina prison farm, stepped in. Winchester engineers paired his short-stroke gas piston design with a Garand-style rotating bolt and operating rod. The resulting arm weighed – and cost – about half as much as a Garand. Fed by a 15-shot detachable box, the M1 Carbine was the most widely manufactured rifle during WW II, with 6.1 million shipped. (Garand production: 5.4 million.)

After the Korean War, ordnance officers sought a short cartridge to replace the .30-06 in infantry rifles and light machine guns. Result: the experimental T-65. Winchester liked it and in 1952 offered it to hunters as the .308 Winchester. Two years later the U.S. Army adopted the round for its M14 battle rifle. In 1957 it became the 7.62×51 NATO. The initial M59 load with 150-grain bullets soon gave way to the M80 with a 147-grain. In 1965 M118 Match loads arrived, firing 173-grain bullets. Tighter groups came with the 118LR and its 175-grain Sierra MatchKing, which stayed supersonic to 1,100 yards.

By the time the M14 rifle was replaced by the M16 in the 1960s the 7.62×51 NATO was used by armies worldwide. Springfield Armory gave the M14 a civilian face with its semi-automatic M1A.

While the 7.62×51 NATO case holds 20 percent less powder than the .30-06’s, muzzle velocities are very close. Traditional 7.62×51 NATO loads sent 150-grain softpoints at 2,820 fps, just 90 fps off .30-06 speed. By the way, .308 and 7.62×51 NATO cases are identical, despite disparities in published breech pressures of loaded ammunition. Throats in .308 and 7.62×51 NATO barrels can differ. To learn more about the differences, click here.

Similar disparities mark the .223 Remington and 5.56×45 NATO, our current infantry round. To learn more about these differences, click here.

In 1957 Gene Stoner of Armalite and Bob Hutton at Guns & Ammo magazine loaded a 55-grain bullet to 3,250 fps for Stoner’s AR-15 rifle. Dubbed the .222 Special, this cartridge had a case .06 longer than the .222’s. It became the .223 in 1959 and five years later was adopted by the Army as the 5.56mm Ball cartridge, M193, for use in Vietnam. In 1980 NATO approved it as the 5.56×45 NATO, substituting an FN-designed 62-grain SS109 boat-tail bullet at 3,100 fps. Original 1-in-14 rifling was now 1-in-12; but this new M855 ammo begged even sharper spin – 1-in-7 twist in M16 rifles. Match loads came in 2002, followed in 2010 by the M855A1, its 62-grain lead-free bullet with a steel penetrator tip.

While the 5.56×45 NATO has given good account at distance, snipers favor more drift-resistant bullets of larger diameter. But that’s a tale for another time.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

177

177